Alexander Dixon’s Hybrid Reflections

Alexander Dixon’s work is capricious. It centres on the meeting place between the artificial and the natural, purposefully displacing the viewer by intersecting environmental planes to create new contextual confinements. In doing so, it allows for multiple spatial and temporal moments to converge, captured in photographs, and then conjoined beyond recognition and laid out on construction metals. According to cultural theorists Geoff Cox and Jacob Lund, this merging of space and time, in relation to the conception of art, acts as a cultural carrier in creating transnational spaces that thematise, represent and become themselves ‘an object of experience.’ This multiplicity of experiential components transgresses the boundaries of rationale, and allows for the emergence of new perspectives, often using the tool of disruption.

Currently on show at Saatchi Gallery, until 11th October 2020, Dixon’s Hybrid Reflections 2 approaches a dissonance towards reality, heavily influenced by paramount texts and mythologies such as Narcissus. Alongside the curators of the show, the artist discusses juxtaposing materials, morphing perceptions, and writing around our contemporary moment.

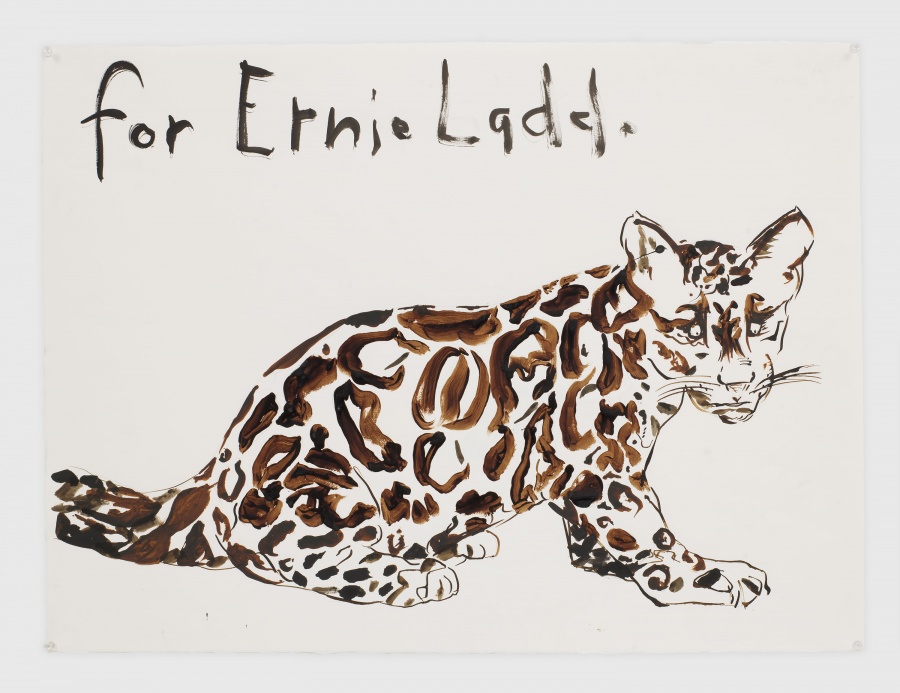

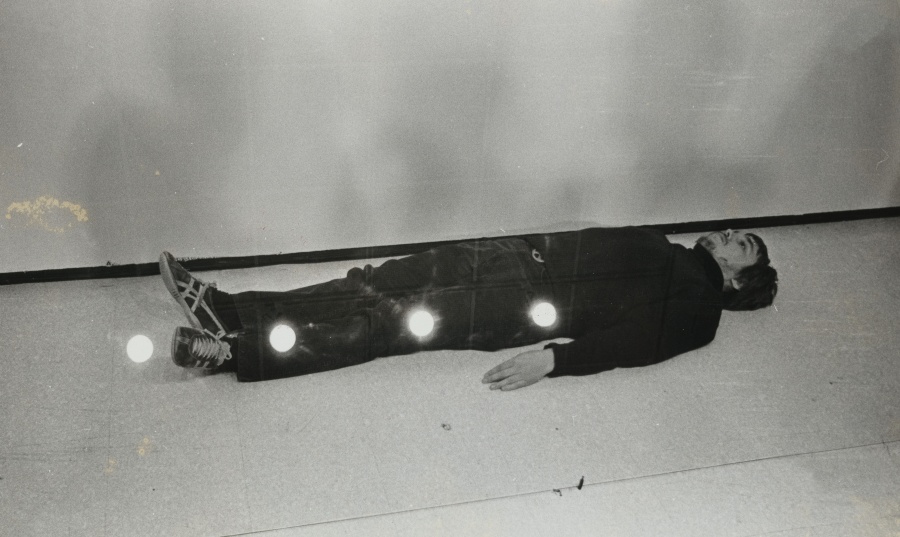

Hybrid Reflections, all images are courtesy of the artist

Mazzy-Mae Green: In Hybrid Reflections, you create composite surfaces by layering images and materials to create one single plane. How does that play into your accompanying prose around Narcissus?

Alexander Dixon: The text accompanying these images works to put the character of Narcissus into the modern moment. And I feel that a large part of that is about this increase in superficiality. When I wrote it, I imagined how it could almost become a dark comedy sketch. I think for me it is about replicating that feeling. I don’t feel that I’m a narcissist, but I do feel interested in narcissism. Coming from the middle of the countryside where I grew up, I have a contrast in my life between there and here. It’s difficult to find alone time in the city, and even when you are walking by yourself, you’re being followed by yourself in a way, too. You have this reflection of yourself on every surface that you come across. It’s something I’m still getting used to. I regularly leave London. And then I come back, of course, but out in the countryside there’s nothing being reflected back at you. It’s just trees and grass.

MG: Your accompanying writing centres on this idea of looking at oneself, and into a mirror, but you can’t actually see into the pieces. It creates a feeling of distortion. Why do this?

AD: Quite often in gallery settings we receive clean-cut texts that pretty much explain what you’re going to get. With this series, the text is more about the transformation of the world around us over time, and this sentiment gives it an ambiguity. It’s also why, when I write, I find myself pulling texts relating to both the past and the future, and that contain a sense of mystery. For my practice more generally, I pull from works such as The Crystal World by J.G. Ballard, Ozymandias by Shelley, and even the future imaginings of the Crystal Chain group, a correspondence of architects that created a chain letter after WW1 around how they imagined the future city to look and feel. These writings then meld with my own thinking around spatiality and architecture, and in particular that of Canary Wharf, from when I would take the overground through there daily. I’ve always found it a bizarre place. Almost dystopian. It’s a mish mash of different time periods, and that’s something that I feel my work reflects.

‘…the areas of disruption for me are what I’m finding the most interesting.’

MG: And how do you start those works? What’s the process?

AD: I always respond to the environment that surrounds me at the time. I find myself connecting to moments or places and I make them my subject. This is often driven by what I’ve been looking at or reading, or thinking about at the time. The two merge. And there’s a constant back-and-forth between being decisive and obsessive, and then letting myself be open to being driven by this idea. I’m interested in material and surface. Here, the flat surface is reflective of the 2D makeup of our surroundings, and it’s important for it to have that quality, but there’s a whole range of other superficial textures that I want to play with.

Greta Voeller: Yes, absolutely. I was thinking, when you initially talked about the references that you’ve used and places that you’ve gone to to take these images, about context. When you look at that image, do you still remember the context in which it was taken? Ultimately through the layering process it creates this extension of that context, like a context within a context. Where were these images taken? And when you look at them, do you remember those places or do they become distorted, too?

AD: In a way. I feel that my view on reality is distorted, and then that comes through in my work. When I take photos, the architecture, nature and people naturally become part of these compositions. And I always feel that I am looking at things from a great distance, but of course it also gives me a personal feeling of dislocation. I rarely feel settled in one place for a long period of time, but when I lock into an idea and become obsessive about it, I feel I can visualise a path for it. For me it always goes back to that idea of things merging in my mind. It’s not so clean cut for me. I find I’m constantly processing. And I pre-visualise what I want to make. But then the piece doesn’t look quite like I imagined in my head, and so I guess there’s a two-way relationship there.

GV: I feel this reflected in the work. There is a real dynamism to it. It changes when you’re looking at it. In the exhibition, we placed Hybrid Reflections 2 high above the midline, and the work almost mutates into something different, watching the viewer as they move around.

AD: I think the subjects that inform the work morph as the piece develops. And I think that has happened again in the exhibition at Saatchi. It was interesting to see the piece placed so high. It felt as if it had morphed again, and that adds another level of disruption. I feel there’s this tightrope walk between places and moments. And I was trying to intertwine these moments in the piece. I like this effect whereby in some instances the algae almost looks like flecks of paint on material – the areas of disruption for me are what I’m finding the most interesting.

Installation view: London Grads Now at Saatchi Gallery (3rd–25th September) © Justin Piperger, 2020, image courtesy Saatchi Gallery, London

MG: There is also an oscillation between contemplation and harsh urbanism in the work, created by your use of soft, pallid colours against the hard materials and processes. This isn’t necessarily something I see in your wider body of work. What shaped this concept?

AD: I think that partly comes down to the subject itself having an associative depth, because of the water, and its materiality, and the process of photography. Merging those components created a painterly image and those hues felt right for that. A lot of my work is more vibrant, but the period in which these pieces were made was different and more static, and I think that this timeline has transferred onto them. They’re quite muted. When I reworked the pieces for your show at Saatchi Gallery, I lent in further to this effect, as I reflected on the past few months. The initial images had references to daily life such as a mobile phone, and I felt this grounded them too much in reality. I wanted them to have a mythical quality. And I wanted them to have an association with painting. It’s about combining and documenting the area where these surfaces meet. I’ve always loved Monet’s Water Lilies and I think those works have influenced Hybrid Reflections in their transference of emotion and questioning onto a landscape. The only difference is the heightened superficiality of my constructed location.

‘… a perfect circle never appears in nature.’

GV: I think that’s very relevant to the way in which Mazzy and I developed the theme of the exhibition. And why we wanted this work in the show. Initially, we began talking about the idea of nostalgia in a broader contemporary sense, and it brought us to the term solastalgia, which is solace and nostalgia combined, and it’s the fear and emotional distress of being confronted with physical environmental change, while simultaneously trying to hold onto something that is knowledgeable to you. From what I’ve just heard, it feels like that emotion resonates very strongly in your practice, and that’s exactly what we wanted to focus on. Instead of thinking about nostalgia as a longing for the past, we looked at it as a way of thinking about continuity and future-thinking.

AD: That resonates with me. Something that changed my outlook on my practice for me was reading a book by Manuel DeLanda called A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History. It made me think differently about engaging with the built environment. His text is intermingled with ideas of nostalgia, or solastalgia, and he blurs the boundaries of everything. He described the city as being an external minimisation of the human skeleton. That blew my mind. That’s a very essential piece of writing to my work.

MG: Does this relate to the circular form and materiality of the work? Can you tell us why you made the choice to print the work in this way?

AD: I wanted it to be a cold, rigid surface. They’re the same materials that you find on a construction site, and so I wanted it to have that materiality to it, but for there to be a dreamlike contrast with the image sitting on top of it. But there’s also a toying with natural forms; a perfect circle never appears in nature. So that also creates that real offset against the background. I worked on printing with my dad for a year, and on a construction site, and that sense of materiality has become an integral part of my practice. Right now, I’m working on a sculptural piece in bright orange, from Bruno Munari’s text that embodies these same sentiments. He has this very playful way of describing things, and in the text he applies the jargon of design to oranges, peas and a rose. I wanted to take an orange apart and imagine its redesign, but also to reflect on the life cycle of an orange, and think about how natural materials decompose, while using non-natural materials that last forever.