Sonic Truth: A Q&A With Raymond Pettibon

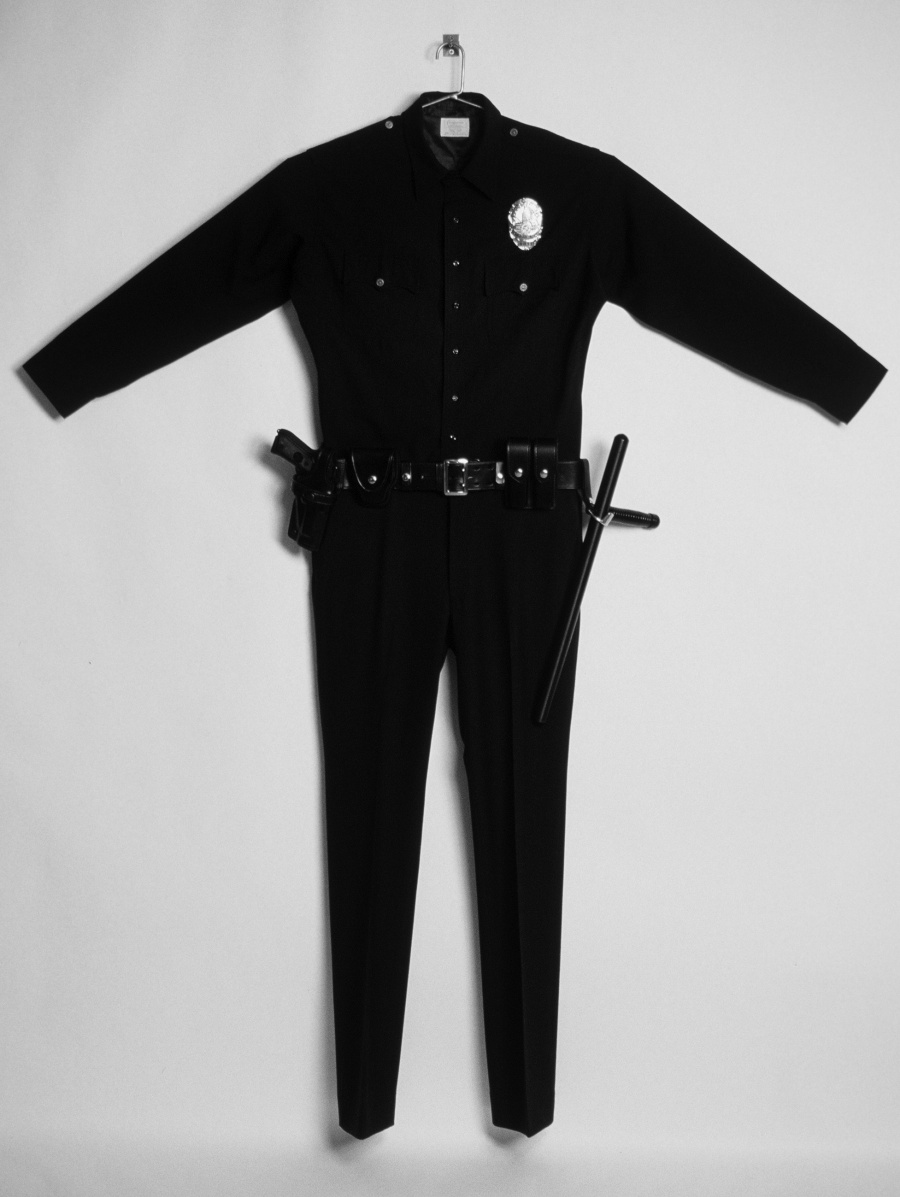

Born in 1957 in Tuscon, Arizon, Raymond Pettibon is an iconic and iconoclastic illustrator and fine artist, famous for his fusion of political critique and hip, punk visual signifiers. His LP covers for both Sonic Youth and Black Flag remain some of the most recognisable countercultural iconography of the twentieth century. Since the 1980s, he has also received major acclaim for his contributions to American contemporary art. He was the subject of a major retrospective, A Pen of All Work, at the New Museum in New York in 2017.

MM What I love about your work is the satire. The ability to harness text and image for social critique harks back to 18th and 19th century artists, and caricaturists such as William Hogarth, Gustave Doré, and Honoré Daumier; but seeing your work today also conjures the framework of social media. All media is social anyway — but which historical precedents inform your work, or are of interest to you?

RP The ones you mention certainly; but also Goya, and [Thomas] Rowlandson, and beyond that, many others. I grew up pre-computer, pre-Facebook, pre-Instagram, and pre-Twitter — that’s a different generation. As far as my art influences are concerned, I can’t get beyond paper. It’s generational. You can’t teach an old dog new tricks.

MM Your work was actually paired with Honoré Daumier’s for a two-person exhibition at Kunst Museum Winterthur earlier this year. As a conversation between two chroniclers, how did you feel about making up one half of this pairing? What intrigues you most about Daumier’s work?

RP Daumier was a formative influence on me. I actually began more or less as political cartoonist — though for the most part, I shy away from caricature, at least to the extend Daumier used it. Politics affords its own caricature: think of Richard Nixon, Lyndon B. Johnson or Donald Trump, for example.

MM Your work also has, for me, an echo of medieval painting — I’m thinking specifically of those works that accompany illustrations of the actions of saints with written passages, creating a relationship between words and images for the benefit of a wider community. Does the medieval strike a chord with you, and do you ever think about an addressee in your work? or are you gunning for obliquity?

RP In the beginning was the Word. I am a student of the Bible and of medieval paintings, not as reflections of the word of God, or of icons, but as literature and art. I don’t contemplate an audience when I make my work. The work finds its own audience, or it doesn’t. I am not proselytizing, nor I am not attempting to convert or appease.

MM There’s also a sense of acceleration in your work—you are highly productive. The language you use is frequently adopted from a multitude of sources in commercial culture as well as classic writers such as Walt Whitman, William Blake, and Marcel Proust. What catches your eye when sourcing this written material? Are you looking for a specific tone, some efficient shorthand, a character, a splinter of narrative?

RP I am not specifically looking for those. It can be almost a material act, the act of reading, rewriting, interpreting, and appropriating. You could call it an active reading. It’s an act of passivity, and it’s also completely the opposite.

MM In terms of your consumption of the images that appear in your paintings – what are your research methods? Where do they tend to come from?

RP Practically anywhere. I can’t say I am of the “plein air painting” school. It can be about drawing from life, although usually, it is mediated by photographs I take. I also use still images from TV or video, and comic books; sometimes it’s simply improvised.

MM I read an interview where you were talking about Whistler’s drawings and etchings being “cross-hatching at its finest.” You said that the technique became something of an exercise for you. Do you often bump into these meta-moments where specific techniques of drawing come to assume content itself?

RP Yes — since cross-hatching is such an intimate and integral part of the practice of drawing, over time it is almost inevitable that it becomes a subject unto itself. Therefore, some of my works are purely “cross-hatchings,” whether improvised, or blown up from other works or figures.

“As far as my art influences are concerned, I can’t get beyond paper.

It’s generational. You can’t teach an old dog new tricks.”

MM Your recent exhibition, Frenchette (2019) at David Zwirner, included many recognisable subjects: Gumby, baseball, animals, and totalitarian dictators. Gumby makes a return as embodied paranoia, as irksome yet sacrosanct artist, as placid guru; there’s a lot of existential Gumby-duality here. Frenchette as a title meanwhile suggests a kind of ironic tourism. Was there a guiding logic to this show, or was it assembled in fragmentation?

RP It was a mix — it wasn’t thought through as one whole. There are motifs that typically reoccur throughout my body of work. As far as the text is concerned, the show was largely improvised rather than drawing from literary sources or influences. I think Art Clokey, the creator of Gumby, will go down as a major 20th century artist. “Frenchette” is a reference to the New York Dolls: “You are not French, you are Frenchette.”

MM You also positioned some surfing scenes almost as a triptych, while one lone drawing of the sea was perhaps the most contemplative. What interests you about the sea as site, symbol, and substance?

RP For me it is about the deluge. Shores without waves depress me. The big wave is about the sublime — the surfer is Turner lashed to the mast.

MM There’s also a dreamlike quality and imaginative dimension to seascapes. Do you recognise dream logic, or nightmare logic, insinuating itself into your drawings?

RP I rarely dream, or at least I don’t remember my dreams. I’ve gone through periods where I dreamed huge waves, and these were perhaps somewhere between a dream and a nightmare. A ride and a wipeout.

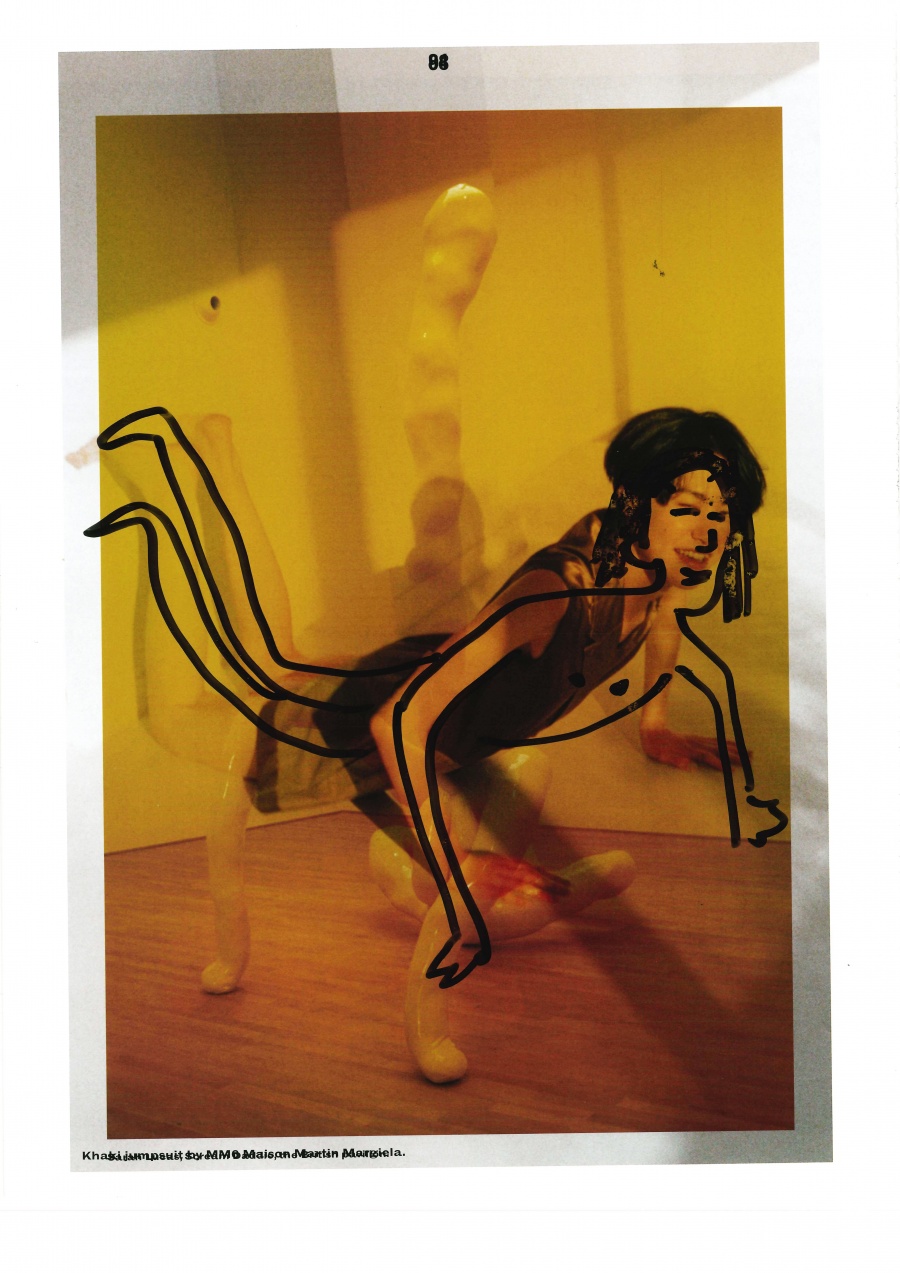

MM Your work is like a shape-shifting carousel — motifs come back, but they present themselves differently. In terms of its overall installation, your work almost resembles collage. What do you think are the possibilities or virtues of collage?

RP I ‘ve been working in collage for half a dozen years or so. My work is associational, so it is not a marked departure for me. An individual drawing can be an aesthetic image, but it can also imply something beyond that — past, present and future. A narrative encompassed in one image.

MM Things are taking shape, one might say of a plan in formulation. Taking something’s shape, one could also say, is the task of the shaman, the mimic or the conman. The scenarios that you create often work themselves up into being almost sculptural — some, coupled together, working toward an aesthetic event. Are you interested in the possibilities of drawing to generate physicality: a building-up, a taking shape?

RP My drawings are meant to suggest. They aren’t reductive, and they aren’t objects; but then words on paper are not, either. They are not mere calligraphy; they suggest worlds and scenes and landscapes. I am not against reading, interpretation, or translation.

MM Do you look on any of your works as successes or failures? Can they be both?

RP I suppose so, though I don’t pretend to be the arbiter of that. There are works I think are more successful than others, although for me it is more about how they resonate on a personal level. There are works that just don’t work out, and those never make it out of the studio. They can lie there for many years, and someday there may be an inspired moment that brings them to life. I do my best, and if I fail, that’s for my audience to decide. I try.

MM I am interested to know more about how you might see words as drawings and drawings as words. Do you always have lines paired with certain images, or is the process more instinctive?

RP It is both instinctive and technical. It is probably easier to demonstrate than to explain. Words taken out of context don’t expire into oblivion. They find new contexts and meanings.

MM Does a Pettibon painting come to life when on the wall, or when inside the pages of printed matter; i.e. when it is held in someone’s hands?

RP I don’t insist on the one or the other. Of course I’d rather live with a Rembrandt than see it in a small reproduction in an art history book, or even see it in passing in a stroll in a museum. But my work has a lot to do with books or reproductions, especially since I started with fanzines of my own construction before I had the opportunity to do exhibitions.

MM Has there been any repetition in the political narratives you’ve been dealing with over the years?

RP The political landscape changes and remains the same. Of course you can’t compare democracy with Nazism and Communism. But America has caught many bodies herself in its history.

MM The categories of pop culture don’t make sense to me today – have the barriers between them broken down completely and if so, are we living in the age of no culture?

RP That could be more telling about the experience of ageing out of pop culture. I don’t think it is necessary to completely divorce pop culture from art. If borders make good neighbours, they can also cause a lot of harm.

MM In 2010 you said: “The distinctions between museums, galleries, books, fanzines, high, low, comics, cartoons, commercial art, fine art are not there for any useful purposes, especially when they’re enforced for marking one’s turf or keeping people out. Entry form above, below, the sides, whatever. My art found its own place.” Where is that place today?

RP The marketplace and the cultural industry are both fluid, something that came from what the economist Schumpeter called “creative destruction.” I was probably referring to the state of drawing as evolving from a means to an end, a study for instance to an end in itself.

MM In 2011, you said in an interview with Mike Kelley: “I’ve been at this for a long time, and I have voluminous amounts of unfinished work in the studio. They’re not all finished at one pass at the drawing board. So when I finally sign the work on the back…do I date it 2011, or 1989 to 2011?” Do you see the works as timeless, or as a record of the day?

RP They are not finished until they are signed. Not everything is done at once, and there are works in progress that can take years to finish. So it is not necessarily one or the other.

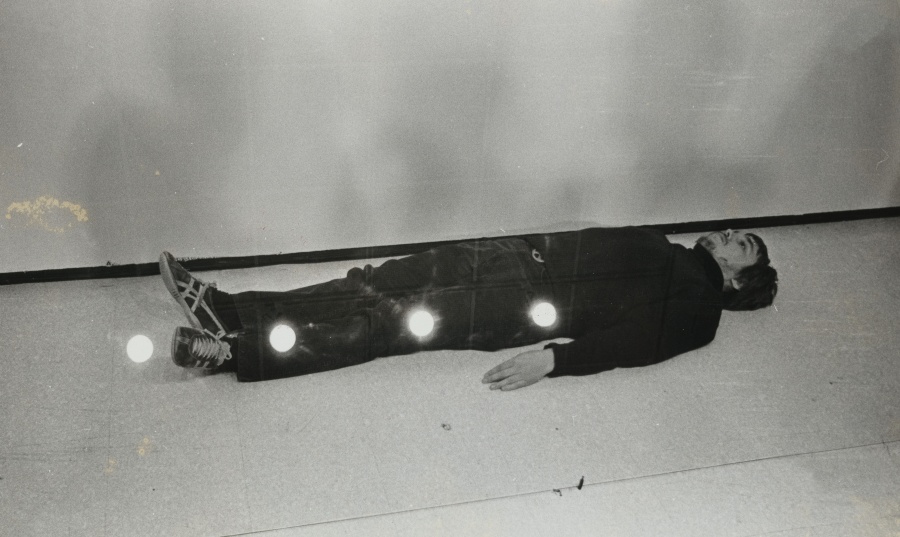

Artist Raymond Pettibon photographed in his studio in New York - Photography by Nick Sethi