You Have to Make a Mark Somewhere, and Then You Can Deal With It

Fifteen years into his five-decade career, Bruce Nauman moved into from Pasadena, California to New Mexico. He’s lived there ever since. “intellectually and emotionally,” he tells Michele De Angelus here, in an interview conducted one year after he arrived in Pecos, “I feel comfortable with [some] distance on the art world.” Evidently, solitude agrees with him; since then, he has become one of our best-loved, most iconic artists.

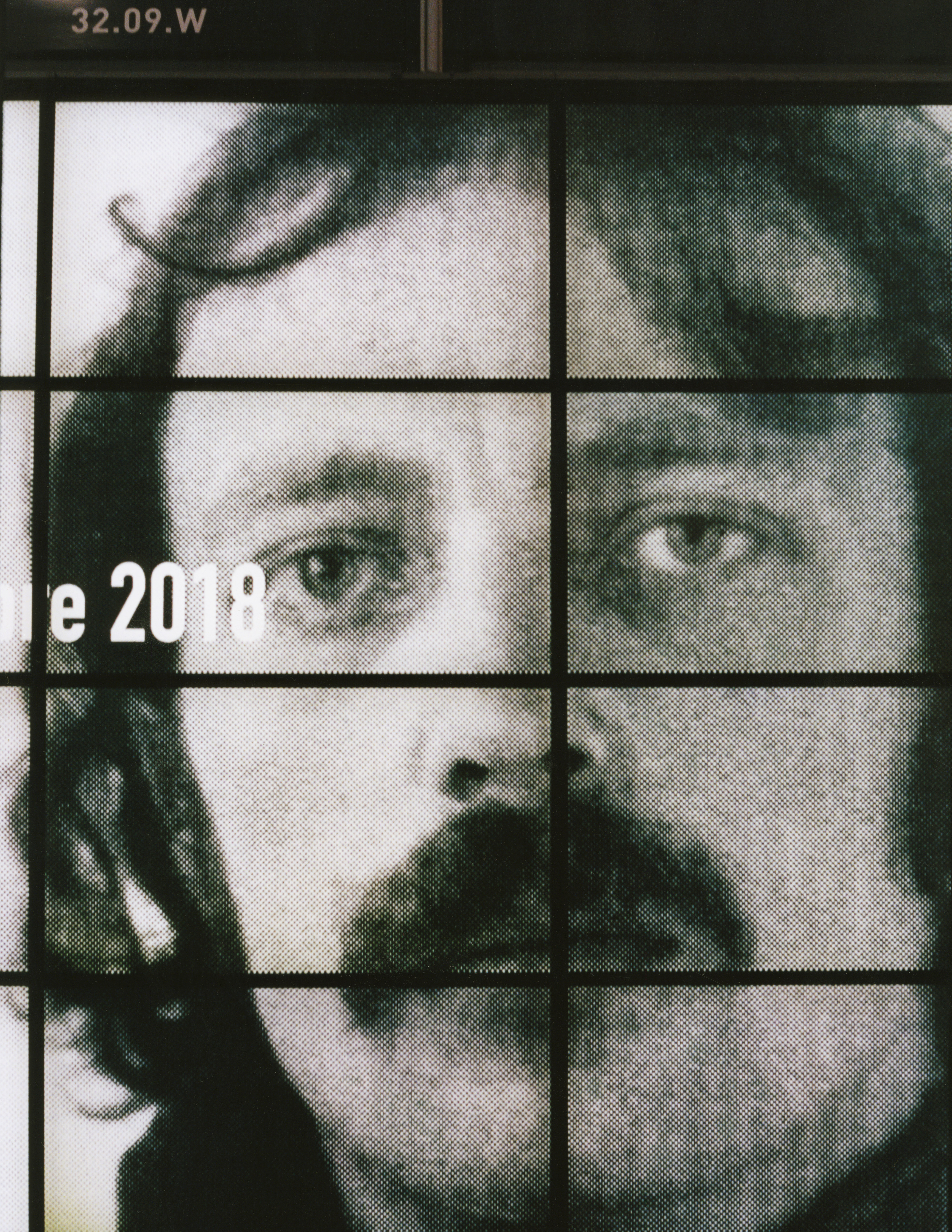

BRUCE NAUMAN

BRUCE NAUMAN

BRUCE NAUMAN

BRUCE NAUMAN

BRUCE NAUMAN

BRUCE NAUMAN

BRUCE NAUMAN

BRUCE NAUMAN

BRUCE NAUMAN

MICHELE DE ANGELUS: Let’s talk about your use of light and neon. Was it interesting technically to you at all, or did you have someone else do all of that?

BRUCE NAUMAN: No, I always had somebody else do it. I think the first use of it that was of any interest was the spiral neon sign, and that was made that way — I made another one that was never as good, but it was a window-shaped wall sign.

MDA: That had words on it also?

BN: Yes. That one said, “The true artist is an amazing luminous fountain.” It was the idea that they would be signs just like any other sign: like a beer sign—

MDA: Coors or Budweiser—

BN: Yes, something like that — that could hang in a window, or on a wall, or whatever. We were talking the other day about having things that related [to] or were based on ordinary objects, like shelves or chairs. One of the pieces I did the first time I was in Germany was called Cast of the Space Under My Chair. It was the chair I had in the apartment I was staying in. I was doing some work for Conrad Fischer. It was a chair that was made after the war; it was all made out of steel, very square, just straight sides and braces underneath. And when we made the cast of the space underneath, it had this very strange [shape] — a little concrete castle, kind of. It was very strange to have this title, also, which was a description of what the thing was in relation to the object, which took on a character of its own. It didn’t read as the space under a chair, but this little toy castle. So those kinds of thoughts were very interesting.

“The true artist is an amazing luminous fountain.”

MDA: The space under, below, or around something — made positive — could have its own identity.

BN: Which I think had come directly out of a de Kooning statement that I read someplace: that when you paint a chair, you don’t paint the chair, you just paint the spaces between the rungs.

MDA: That’s what was happening in that shelf that was sinking into the wall.

BN: Yes— well, that and then it comes out of the same idea as a lot of the Futurist things, of speeding through space.

MDA: What about those light photographs, like Traps for Henry Moore? That’s a use of light; but the whole title implies a spacial existence. Tell me about those.

BN: And I tried to make the drawing three-dimensional. What am I supposed to tell you?

MDA: You’re supposed to just tell me what you were thinking of when they came into being. Those are really eerie to me, probably because of the title. In a way, that’s Futurist because it’s like movement in time that isn’t substantial. Why Henry Moore?

BN: I did quite a few drawings, and several pieces, that related to Henry or had him in the titles; it seems to me that it was a period when a number of English sculptors were gaining some prominence. There were quite a few, at the time — and some painters, too. And a lot of them didn’t care for Henry’s work; which I was not particularly fond of myself, anyway.

MDA : Did you see it as these people being bound by his success?

BN : No, I don’t know that I had that particular view — but there certainly was that. If you didn’t do Henry if you worked like that, it was very hard to get any acceptance, I’m sure.

MDA : Why light traps?

BN : Because they were made with light. I don’t really remember all my feelings about those.

MDA : In the image were you trapped in the light — was that it?

BN : No.

MDA : There’s one piece about Henry Moore, and it’s like a case.

BN : It’s a drawing. It’s a storage capsule.

MDA : Yes, Seated Storage Capsule for Henry Moore. It’s so Egyptian.

BN : Well, I was also trying to make the drawing somewhat like Henry’s Subway — Underground — drawings. And I also had the idea that they would need Henry sooner or later, because he wasn’t bad; he was a good enough artist, and they should keep him around. They shouldn’t dump him just because a bunch of other stuff is going on. And so I sort of invented a whole… mythology about all that, I suppose you’d call it.

MDA : So these are kind of fantasy drawings? You’ve made other capsules — like real life, storage capsules. A storage capsule for the neon templates of your body. When did your use of holograms begin: when did you get involved with them?

BN : That was 1968 or so.

MDA : How did that happen? Was it an extension of the photographs?

BN : Well, yes — it came out of the performance things; and the idea of making faces was the first group. So they were made as photographs first, and that wasn’t quite satisfactory. Then I did some as short films, film loops, and eventually — I don’t remember where I came across the idea, perhaps in Scientific American or someplace — I found a company to do the work.

MDA: How did that change the quality of the images?

BN: Well, they became three-dimensional images. They were much more sculptural.

MDA: But they were still static.

BN: They were static, yes.

MDA: Did you see those as being self-portraits, essentially, or more about human gesture?

BN: More about human gestures; although I don’t know. I’ve always worked pretty much alone, even in this case where somebody else was making the work. I used myself as the subject matter. I’m not sure if I could or would have, at the time, used someone else, or let somebody else do that much.

Extracted from: Oral history interview with Bruce Nauman, May 27th, 1980, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Read more in Modern Matter issue 13, The Anti Issue.