The Kind of Joy That’s Erupting out of Ruined Buildings

28.05.18 | Article by Michele Robecchi | Art, culture, interview | MM12 Click to buy

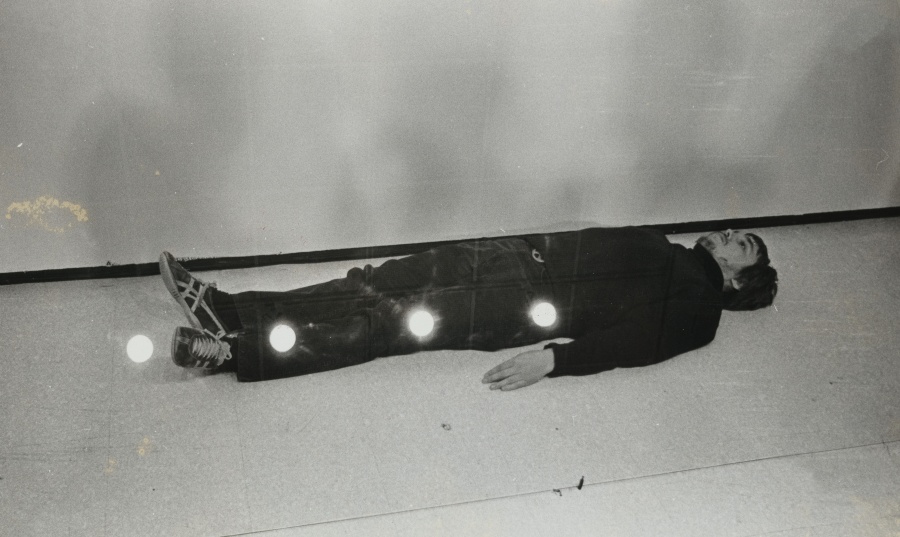

Michele Robecchi: Your film Dream English Kid 1964–1999 (2015) is an attempt to rebuild your life through materials available on the Internet. There is an element of danger in trying to deal with the past in that way. It could have triggered unwanted recollections and associations, or even modify the chronological order of your own perception of certain events. Was it a painful process to put it together?

Mark Leckey: In a way, I was hoping it would be more painful and that it would extract more from me. Weirdly, in the end, it was kind of numbing. I didn’t make it to be cathartic –I didn’t expect to resolve anything. When I made Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999) it was almost the same. It was just this urge to jettison stuff, because the psychic buildup is too great. It was also a situation when technology provided a device that allowed me to explore that.

MR: Because the Internet didn’t exist in the same way, there is a tangible difference between the way information pre- and post-2001 is processed and presented. There are materials that have been created with the purpose of feeding the platform and materials that have to be collected from the past. Did you feel this discrepancy while you were working on the film?

ML: What’s interesting in terms of what you’re saying is that I’ve found a weird data black hole in the 1990s. The film starts in the 1960s, then there are the 1970s, the 1980s, but then when it gets to the 1990s, everything becomes quite obscure and unspecific. I found it hard to gather materials from then. It did seem objectively less rich than the other periods. Maybe the 1990s haven’t been resolved yet. It’s still kind of jelly. It was a transitional time.

I think there will be a very intense nostalgia for the 1990s, because it seems — whether it’s true or not — to present itself as the last hopeful decade. It’s where everything seemed to align, in a sense, before it all collapsed. I don’t think that’s necessarily true, because there were obviously events that took place in the 1990s which were just as horrific as the ones that are happening now, but just in terms of my own memory, the 1990s became very white, clean and detoxified. There was an anxiety about the end of the 1990s. There was Y2K and all that pre-millennium stuff, but then on the other side, there was this idea that we were going to cleanse ourselves of the sins of the 20th century. It was seen as a new horizon.

MR: That pre-millennium tension generated a lot of sub-cultural phenomena though. Britpop, Trip-hop, Grunge. Grunge in particular was interesting because it made heavier, guitar-oriented music more palatable.

ML: And that’s where I think it all went wrong. You’ve got raves, you’ve got jungle and drum and bass, which is this really futuristic, progressive kind of direction that music was taking; and then you get Britpop and Grunge which are essentially retrogressive. They were looking backwards but I think they won, in the end.

MR: But when it comes to forms like Hardcore, don’t you think that that kind of energy and purity can only be sustained for a limited amount of time?

ML: Maybe. The thing that reminds me most of Hardcore now is Grime. The analogy is there – it’s very underground, autonomous and self-sustaining. It’s difficult to talk about Hardcore. I always end up having these conversations about subcultures – where they went and if they still exist. But one, I’m too old to know that; And two, I think there is a subculture at the moment, which is what the alt-right have emerged from, which is 4 Chan, and all that kind of stuff. That’s where subculture has gone. And I know nothing of that. I’m old enough to be their father. That’s the age-difference.

MR: I guess people feel compelled to bring up subcultures with you all the time because they are so rooted in some of your early work.

ML: That’s fair enough. But whenever we talk about this, I can only talk about it in the way that Dream English Kid 1964–1999 was about. I sort of stop in 1999. The 21st century is a time when subcultures are beyond me. I’ve left their orbit.

“I look back to disco and early hip-hop, and all of the rest of it and I see a very joyous time – the kind of joy that’s erupting out of literally burnt, bombed, ruined buildings.”

MR: But they must still be informing who you are today?

ML: They do. I look back to disco and early hip-hop, and all of the rest of it and I see a very joyous time – the kind of joy that’s erupting out of literally burnt, bombed, ruined buildings… There’s something I keep thinking about, though. I don’t know how much of this is something that I believe, but at the moment there’s a compulsion towards the idea that art has become more political. Art and music have become more polemical and about protest. And my experience of protest music, political culture and art is sort of summed up by something like Red Wedge — do you remember them?

MR: Yes. Billy Bragg, Paul Weller and the likes.

ML: Exactly. When I was 18, Red Wedge meant nothing to me. The audience that it was speaking to wasn’t me. It was trying to build a bridge between music and politics but it didn’t reach me. What did affect me was dance music. I absorbed the message of dance culture, which was that it’s an open house that includes everybody. It was interracial, inter-sexual, free. And I feel now that the division between this reactionary, patriarchal, right wing insurgence and [the rest of culture] is opposing the message that disco filtered out to my generation, and to generations after, which is that idea of inclusion and liberalism. Disco was kind of liberalism to a 4:4 beat, right? And the argument against disco, from punk and from everywhere else, was that all it did was reflect capitalism. That it was aspirational but mostly that it was escapist. But for me, under its umbrella was a much greater, much more powerful kind of ideology. I learned a lot through it.

“I think I’m kind of pro-escapism.”

I realise that’s kind of a paradox, because the idea now is that art should become more direct, or more instrumentalised, but I think I’m kind of pro-escapism. Escapism comes about because the reality is too great to bear. And that reality will always seep in. Politics was always in disco, and it was always in rave. It just wasn’t so immediate. It wasn’t the face of it. The face of it was a big smiley, happy thing, but behind that were all these needs that were politically determined.

Read more in Modern Matter issue 12, Colour Model.