Nose Best

1.06.19 | Article by Philippa Snow | Art, Magazine | MM11 Click to buy

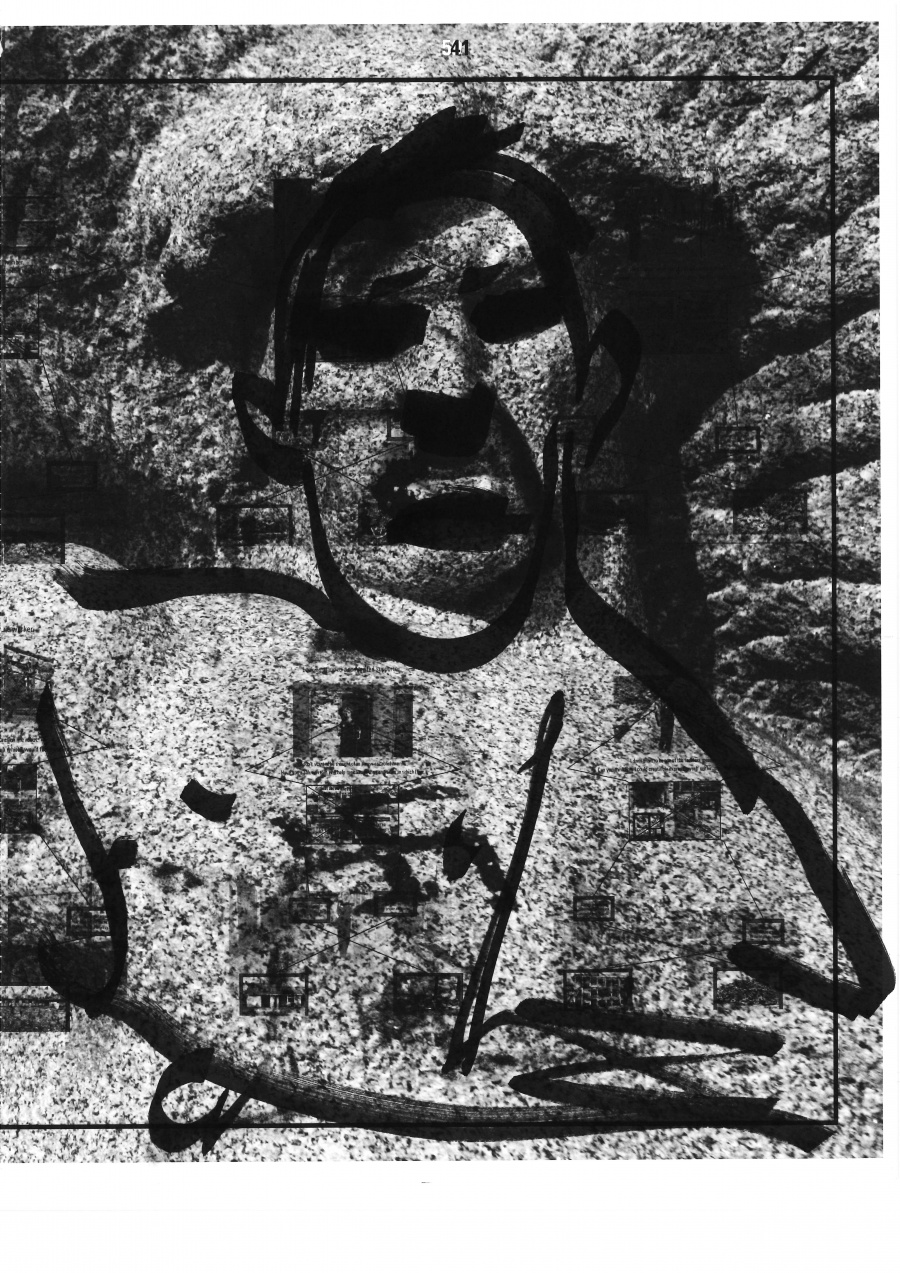

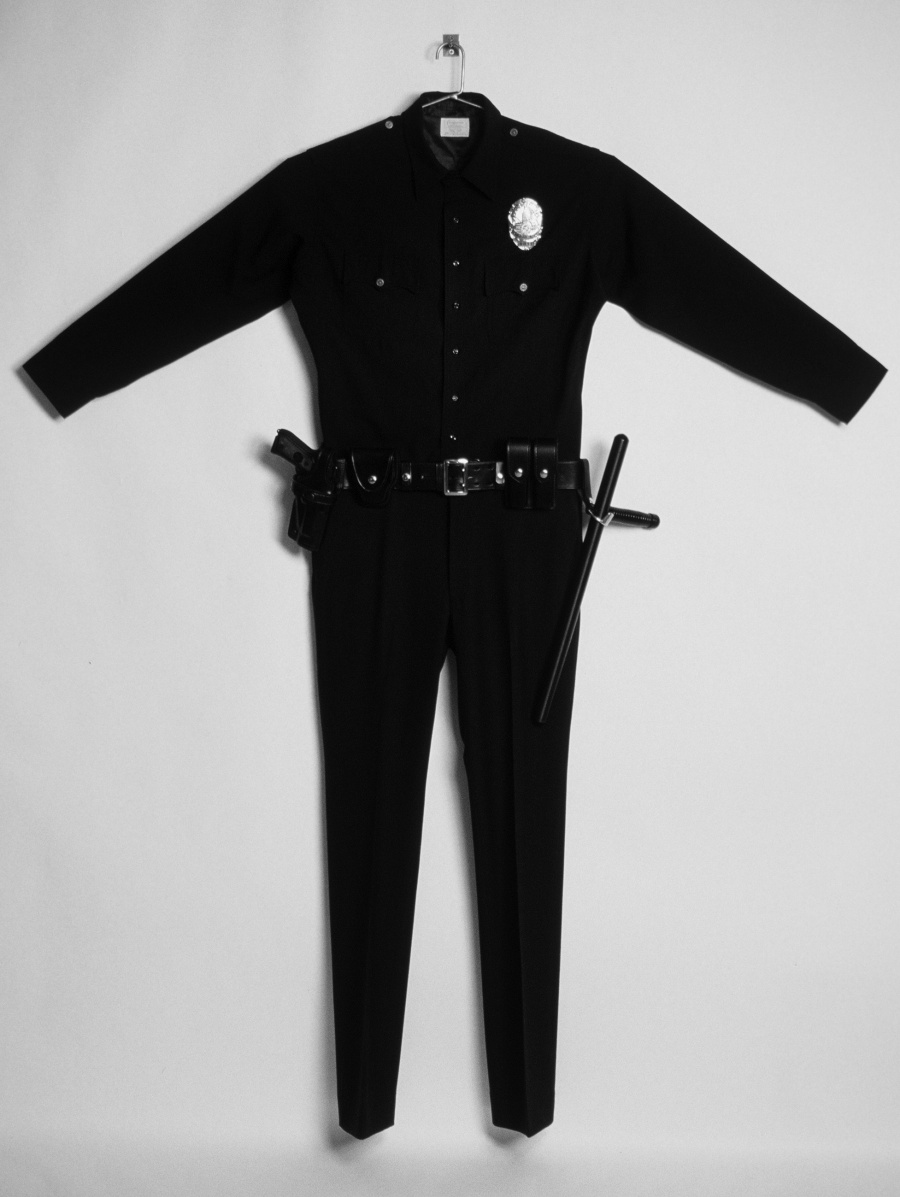

Modern Matter Selects the Best of John Baldessari’s Classic Nose Motif From His Archives

Courtesy of Sprueth Magers Gallery

Noses & Ears, Etc.: The Gemini Series: Face with Nose. and (Green) Ear, 2006.

“I’ve always considered myself an assembly of parts. I’m not unified”

A truly modern image is, typically, one that’s been manipulated. This is also true of one’s self-image. There’s no truer way to learn that it’s the nose that defines the face than to meet somebody who’s purchased a new one as, most often, the change is as plain as — etc. etc. You meet a construction instead of a person, though sometimes this makes them more interesting.

“I wish I had a twin,” Joan Rivers once said, “so I could know what I’d look like without plastic surgery.” Most of us have to make do with that terrible knowledge the whole of our lives, which means it’s tempting to think of being able to cut out or cut or erase our worst features; the good, we might isolate. We might choose to draw a veil over everything else and allow our best parts to define us; and we might, if we are smart enough, call this an art form. Beginning with 1965’s droll pun, God Nose — and, as we’re made in His image, we have to assume that He has one — the Californian artist John Baldessari has turned the nose into a signature: paintings, collage, sculpture, books and installations fetishise the feature into a something like a logo. In iconic works like Cutting Ribbon, Man In Wheelchair, Paintings (Version #2), which block black-and-white photographs with censor circles, he shows what a familiar face might look like with no nose (or face) at all.

Nose/Silhouette: Colors

“That’s what people, when they think about me, think [of]” he admitted in an interview with The Financial Times. “I only did it for a few years, but it sticks. What are you going to do?” Even profiles of the artist himself aren’t above talking physicality — “For a very long time,” says David Salle, “John Baldessari had the distinction of being the tallest serious artist in the world (he is 6’7”). To paraphrase the writer A.J. Liebling, he was taller than anyone more serious, and more serious than anyone taller.” “For Baldessari,” explains the release for a show at Spruth Magers Gallery in 2009, for which the artist presented a tableau vivant that included an ear-shaped sofa and nose-shaped sconces, “representing the face and its features offers ways of exploring myriad conceptual questions, including the problem of perception and the physiological basis of experience, and the constitutive role of faces in forging (and erasing) human identities and selfhoods.” Unable to resist a further visual joke, he filled the sconces — the noses — with flowers. More than merely symbolic, of course he also recognises the nose as sensory; art being governed by both sense and senses. The instinct and the intellect converge in it.

Noses & Ears, Etc.: Blood, Fist, And Head (With Nose And Ears), 2006.

Noses and Ears, Etc., (Part Three): Two Altered Persons (One with Red Nose), 2007.

“I think I started all these body part things when I had the retrospective show in Vienna,” Baldessari told Parkett in the same year. “Ears, a nose, a thumbnail, and a thumb. I’d done them because I was getting billboard material from this friend I’d gone to school with. I thought it might be interesting to use any old leftover stuff. And they would paste them up by section. I just loved unfolding the packages and seeing what had been randomly sliced. Once I got an ear and I just painted over it completely. And then there was another face that I remember just slicing up. Once installed together they formed a head. And I thought, God, those are not so bad, I think I’ll go back and do that again, but in a new way… I don’t think I want lips. They’re too beautiful. They detach too well. I know noses from literature and music, and lips from, like, Man Ray. And eyeballs are omnipresent. I wanted to do something that would look kind of weird and detached.”

Noses & Ears, Etc.: Fountain Sculpture And Head (With Nose And Ears), 2006.

“Kind of weird and detached” is a good definition for modern art’s métier. It is also, more or less exactly, how these noses look. In isolation, they still look for a space to define. If the eyes are often described as being the windows to the soul, what does that make the nose? A window to — well, according to tedious scientific comment, the lungs: but then whoever made art and still cared about science? The Golden Ratio suggests that a person’s looks are governed by simple arithmetic: noses whose lines are perfect are, therefore, like gold dust. They open doors rather than windows. Attuned to popular culture, Baldessari knows that it’s the nose that has it: one of the funniest-or-most-absurd artists working, he also knows it’s the most inherently odd of our features. Adding the nose motif to a line of skateboards by the hip skate company Supreme, he mused to The New Yorker: “Maybe because I’m tall and gangly, I’ve always considered myself an assembly of parts. I’m not unified. But you don’t need the whole thing. Hollywood has always taken advantage of this — they show us the part, and that’s all we need.”

Some things are better when viewed in installments; the piece in question, by accident and not design, fell in a column called ‘Artist’s Picks’. This made each board a picked nose. I doubt the joke was lost on him. “John is [the] most pure [artist] because he understands that art is based on the relationship between human beings,” Lawrence Weiner said in 1984, “and that we, as Americans, understand our relationship to the world through various media. We think of any unknown situation in terms of something we’ve seen at the movies.” And when was the last time anybody saw a real nose at the movies, aside, perhaps, from in the audience? Hyperreal noses, perhaps, where ‘hyperreal’ is defined by Baudrillard as “the generation by models of a real without origin or reality.” (In a few select cases, one might see surreal ones, admittedly — these are the ones that get circled in magazines, and are less fully realised artworks than bad sketches.

Read more on Modern Matter issue 11, American Masters

God Nose, 2007.