Kunst Talk: Rebecca Ackroyd in Conversation with Alexandra da Cunha

Courtesy by Galleri Opdahl Rebecca Ackroyd

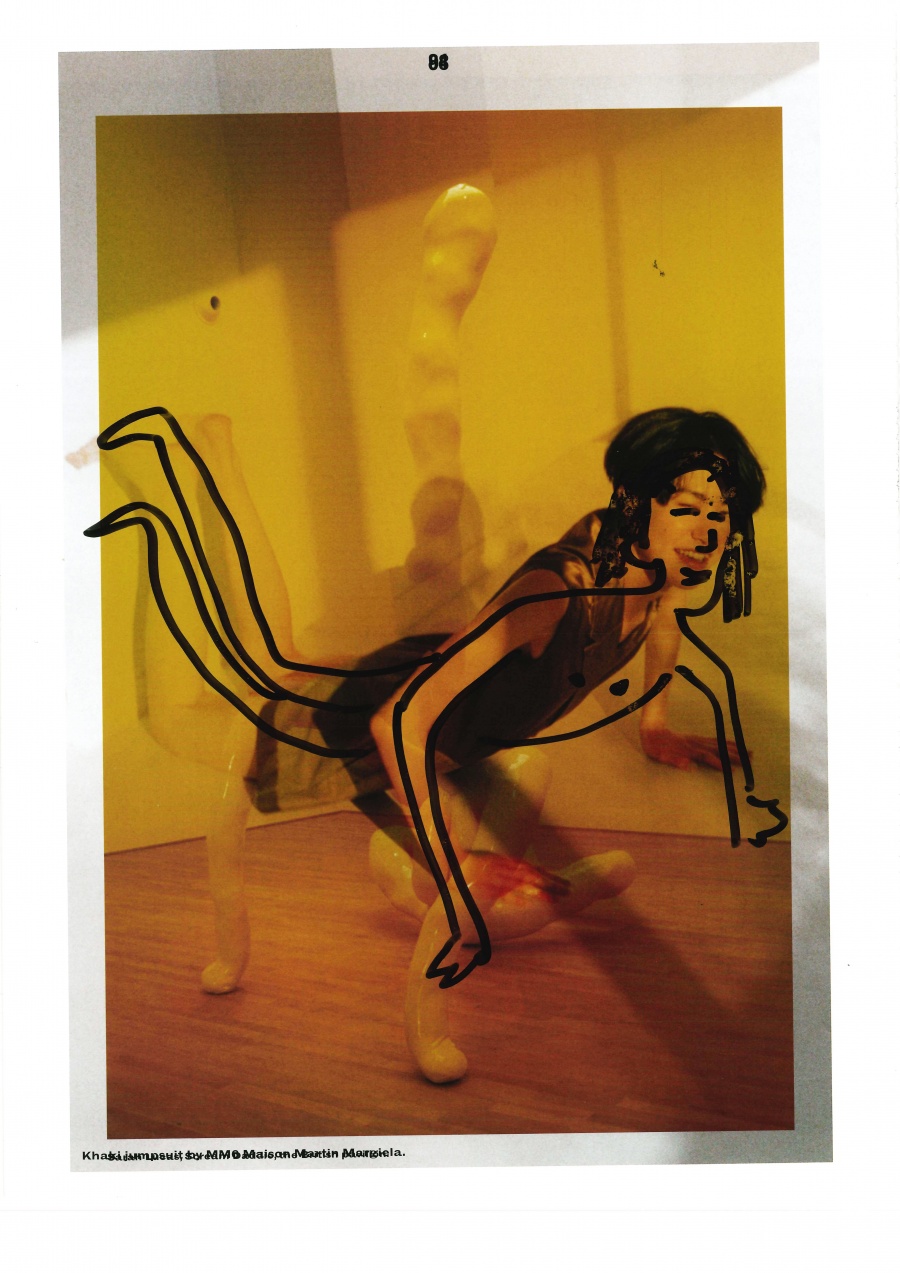

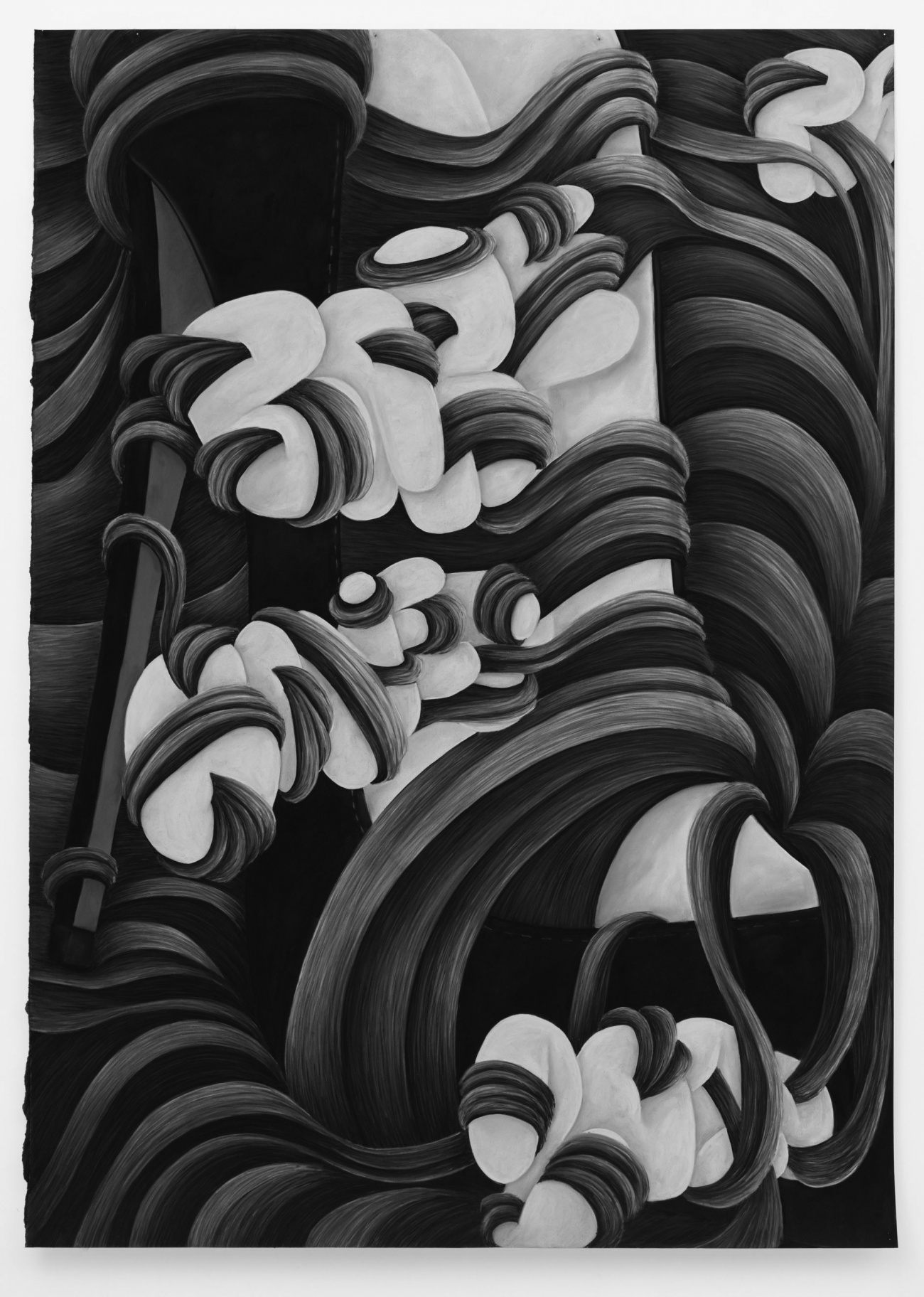

The materials an artist chooses affect not only the look and feel of their work, but also the way in which they make it. Rebecca Ackroyd and Alexandre da Cunha both make selections that shape their processes. In Ackroyd’s work, she creates ghostly and unsettling atmospheres through a quick, urgent process of loosely applied materials, from chicken wire, fiberglass, and plaster bandages. For Da Cunha, his methods of displacing and re-contextualising everyday objects have a more conceptual understanding – naturally slower. Often, they involve repurposing mass-produced objects to fit a minimalist aesthetic, heavy with symbolism.

○

Alexandre da Cunha:

We discussed this briefly once, but I like the way you combine quite difficult materials together. I don’t have in mind many artists making elegant sculptures from chicken wire, for example. And you do that. So I feel like there’s that choice of materials and textures. Can you tell me more about this process of material selection and what the relationship between these components is?

□

Rebecca Ackroyd:

I do tend to work with very specific materials because of their properties. Chicken wire and plaster bandage, for example, are rudimentary and fast materials, meaning I can realise ideas quickly. Because the earlier works I was making were very architectural, like venting shafts with feet and hands on the end, these giant limbs that intercepted a space, and it was really important to me that I constructed these new pieces within a few days. I wanted these things to grow and then be dismantled straight away. That’s how I started working in that way, and then that morphed into the Perspex figures and windows, which is another conversation about bodies, insides and outsides. For the resin pieces, I never wanted to work with resin ever again because I don’t like how toxic it is, but I wanted to make these works that were like ghostly images, so they have a very different feel to the plaster works, but for those the transparency was really important to the body of work, and I wanted them to be glowing and paper-like, they had to have a sense of fragility and temporality. They emerged from this initial idea of a ghost sculpture that tied in narratives of memory and nostalgia and how that becomes fragmented through time. I also like the idea of casting different parts of my body at this age and then thinking that in however many years I might cast again and the conversation will be completely different. So, I like having these markers of fleeting time. The way that I cast the figures at the moment is fast and unpredictable, so I want them to retain that sense of precariousness and look papery and falling apart… and sometimes they do!

○

ADC:

That’s something that’s really interesting to me because with your images I feel a great level of contrast between the drawings and the sculptures, and then here when you speak of resin and transparency, and one thing that gripped me is how the drawings are so different to this. They’re very opaque… There’s not much space to see the paper because you cover the entire surface. They feel like independent bodies of work. One is the translucent sculpture, and one is the surface of the drawing.

∆

RA:

I’ve been thinking about this, because I wanted to make some drawings recently that are more translucent and layered, but the soft pastels I use have become very specific to that body of work and they have a very dense consistency that can be worked quickly. A bit like the sculptures, the drawings have an immediacy to them, and have a matte, velvety surface that absorbs light and can be manipulated by hand.

□

ADC:

And do you see them as separate to the sculptures?

○

RA:

In some ways… I see them occupying the same headspace as certain bodies of work, such as the plaster works, but they operate in a completely different way to the casts I make. I think they’re very different processes.

Sculpture is a very physical and material process, and sometimes you just need to do something that is spontaneous and unplanned…

and for me the drawings reflect a psychological process that’s more about freedom. They started as something very private that I didn’t show, and gradually they became a bigger part of my practice. […] I felt like they didn’t feel cohesive to my body of work, but then I just started showing them because I thought that otherwise I would end up with a whole different side to my practice that I never showed because I was worried it didn’t make sense. I remember that we once discussed the idea of things having to make sense, and I remember you saying: “Why do you have to have everything having a conversation, maybe certain elements of your work can be having an argument instead.” And that’s really stuck with me.

∆

ADC:

I think I’ve been trying to do this with my own work, and maybe that’s why I told you this back then. I find it important to create a level of tension between things. I think we have a tendency to harmonise everything, and it’s very good when you have clashes that naturally appear in the work. And instead of forcing them to adhere to a style, it’s good to let that happen.

□

RA:

I also feel that people get caught up on wanting assurance from art that it has clear meaning. Someone once wrote that my work didn’t make sense, and I don’t really mind that it doesn’t always make sense. It’s interesting, though, that people want a concise idea, while for me I’m interested in many things at one time and that’s how I think, and it’s how I work. […] When I put on a show it’s always about a feeling, rather than an idea, a specific feeling or sense of something that I’m trying to articulate, and then the works develop through that feeling.

□

ADC:

When I look at your work, I feel that there’s a very particular language. I don’t have the feeling that it was made in a certain time, or for a certain generation. It feels almost old school. I was thinking today that your work has this aura to me in that it looks young but it has an old soul. […] It’s not necessarily concerned with now, or a specific context. I’m wondering, do you feel like your references are quite old school and classic?

○

RA:

I think it’s a mixture. There are artists who have obviously influenced my work like Isa Genzken, Franz West or Louise Bourgeois, and then I suppose I engage with my contemporaries and their work in a different way. I’ll go to shows of friends and fellow artists and absolutely love the work, but it will be more the energy that inspires me. The things that I bring into my work are much more outside of art these days. Like I’m really interested in psychoanalysis, and also things like the works that I made recently, the casts and resin works, a lot of those were talking about the past in a way because in them I’m wearing my mum’s knee-high boots and that specifically references memory and time. It’s difficult because I feel like I know what you mean about an old school approach or feeling, but I think maybe it comes more from the fact that people don’t really make so much sculpture anymore.

∆

ADC:

I think that could be true, or that the nature of it has changed.

□

RA:

I always have these ambitions for how complex and layered a work could be and it ends up being a simple gesture, and I think it’s about accepting what kind of artist you are. You can’t be everything and do everything and you need to make things in your way.

□

ADC:

I like what you said about accepting the artist you are.

∆

RA:

Do you find that too?

□

ADC:

Well I haven’t really accepted it yet. I’m still struggling. But I have accepted that for me it’s about that struggle. And I think it’s also about accepting being an artist. Often, I’m confused about my profession: I find it exciting and surprising to have ended up being an artist. I think it’s a huge part of this work, acceptance.

○

RA:

Often when I make work, I find I have to enter a completely private space to be able to do this. You have the ideas and ambitions, and then the show is the show, and there’s the realisation of those pieces. The process makes you look in the mirror a lot, figuratively speaking of course.

∆

ADC:

I follow you on Instagram, and I find you very active, and politically engaged. You’re vocal and post things about politics. Does politics play a part in this process for you?

□

RA:

I have made certain works that are directly political. For example, I made a work when Trump was elected called We Have Your Children. It was a photograph of me with these hairy monster gloves, grabbing my crotch. And actually for that exhibition, the room had this pub carpet that reflected an idea of national identity, so there was this sense of not being able to escape where I’m from suddenly, especially after the referendum. But generally I think this is less overt in my work. These references exist within a much bigger conversation about the work and the ideas I explore within that. And the process of making, and

… for me there always has to be a sense of the unknown in the making, and not really knowing. Following a thread and not knowing where it’s going, because then surprising things happen, and that’s where you turn corners as an artist.

So in that way it’s quite hard to be overtly political because the process is very psychological, and for me that’s important. But then there’s the occasional piece of direct content that enters the work that’s very political. And I’m happy with that. It’s another layer of opposition and tension.

○

ADC:

And what are you working on right now?

∆

RA:

I’m currently working on a show for Lock Up International, which is run by my friend Lewis Teague Wright, who is an artist. It’s always in a different storage space, and he’s done them all over the world. The one I’m in is opening in October at the Barbican, so I’m currently making work for that. My next solo show will be at Peres Projects in January. What about you?

□

ADC:

I’ve been working on a show at Thomas Dane Gallery in Naples for a long time. So I’m just finishing final pieces for that show and working on a large outdoor commission that opens in Plymouth at a new public space called The Box. Both shows open in September.