I Want to Do as I like; Invent My Own Interests

28.06.18 | Article by Bruce Hooton | Art, culture, interview | MM14 Click to buy

Bruce Hooton: I don’t understand the new geometric art. Norman Mailer complained the other day in the New York Times about the square look of things. You know, everything is simplified and square, too simplified.

Donald Judd: Well, I really only know about myself, my reasons for doing it. They certainly aren’t connected with the old geometric art. My work isn’t geometric in that sense. One of the reasons, I guess, that my stuff is geometric is that I want it to be simple; also I want it to be non-naturalistic, non-imagistic, and non-expressionistic. The simplicity goes all the way back through my other paintings, almost to when I first started working.

BH: Where did you first work?

DJ: I was born in Missouri and lived around the Middle West, then moved to Philadelphia during World War II — no, just before it, before Pearl Harbor. And then we moved to New Jersey and I went to the Art Students League.

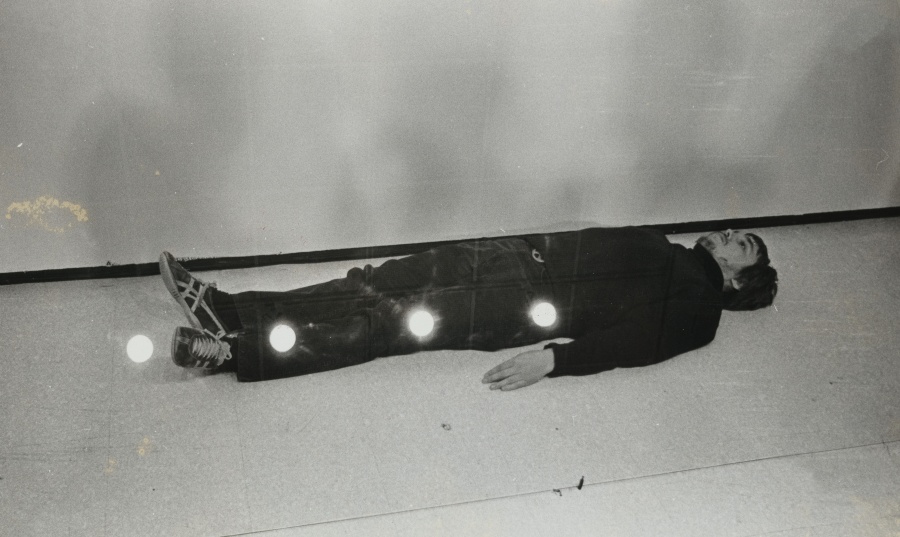

Donald Judd, untitled, 1975. (Image: Anne Collier © Judd Foundation)

BH: How long did you study at the Art Students League?

DJ: For about three years–three and a half years.

BH: With whom?

DJ: With Louis Bouché the first two years; one year with Louis Bosa; about a year with Will Barnet; and summers with several people — Marsh, Hale and Johnson. I don’t know if you remember him; he used to teach contour drawing. I don’t remember his first name; he’s dead now. And Bernard Klonis. Yes, I went to school here. I began studying art in ’48 or so, and then I moved here in 1953. Before that I commuted in from New Jersey to save money because I was doing both Columbia and the Art Students League.

“One of the reasons that my stuff is geometric is that I want it to be simple. Also — I want it to be non-naturalistic, non-imagistic, and non-expressionistic.”

BH: Did you take a degree at Columbia?

DJ: Yes.

BH: In art?

DJ: In philosophy. I figured I had a major in effect at the League.

BH: When did you first meet Reinhardt?

DJ: A couple of years ago.

BH: Were you painting or working more or less the same way before you met him?

DJ: I don’t remember being directly influenced by him. I admired his work, but also that of quite a few other people. One thing is that I was a painter until maybe ’61 or ’62 — I’ll have to figure out the dates — and then I started doing three-dimensional things. The paintings are not exactly geometric, but it’s there. Geometric art as such doesn’t mean all that much to me. A lot of the people I admire aren’t doing it. I don’t feel the connection is that way.

BH: A drawing I saw of yours had a kind of inverted Stonehenge feeling. There was a certain monumentality even though….

DJ: It was blatant.

BH: What?

DJ: It is a post and lintel arrangement.

BH: There’s no kind of philosophical point to the whole thing? I mean, what would one say if one decides to cut out certain things in the same way? One decides to throw paint; one decides not to throw paint; or to simplify things.

DJ: Well, I am not interested in the kind of expression that you have when you paint a painting with brush strokes. It’s all right, but it’s already done and I want to do something new. I didn’t want to get into something which is played out and narrow. I want to do as I like, invent my own interests. Of course, that doesn’t mean that people who, like Newman, still paint are worn out. But I think that’s a particular kind of experience involving a certain immediacy between you and the canvas, you and the particular kind of experience of that particular moment. I think what I’m trying to deal with is something more long range than that in a way, more obscure perhaps, more involved with things that happen over a longer time perhaps. At least it’s another area of experience.

BH: In other words, you’re trying to lay the foundation for thought. I mean, one might say that you try to kind of stop time for a minute, or stop certainly Abstract Expressionism in its lesser form of a great teaching gimmick across the country, because anybody can do it. It’s like a great thought — anybody can throw paint.

DJ: Well, that can be said of drawing or anything. Anybody can do it if it isn’t too good. But I’m not against Abstract Expressionism. I think it’s just as difficult and just as good as other forms have been. As usual, it had a superfluous number of followers.

Donald Judd, untitled, 1992. (Image: Alex Marks © Judd Foundation)

Donald Judd, untitled, 1991. (Image: Alex Marks © Judd Foundation)

BH: As any group does.

DJ: Yes, and that certainly helped to run it down.

BH: It gave ammunition to people who were totally against it.

DJ: Yes, and it was accepted too rigidly and I think that…

BH: That’s actually what killed it.

DJ: No, several of the main people failed. I think Kline‘s painting went down hill, and de Kooning‘s. Pollock died, of course. And Pollock, Kline and de Kooning are considered the typical Expressionists. But even if Pollock had lived and de Kooning had kept up his work, new things would have come along. Those people seem pretty tolerant. Now it’s only some writers and followers who are rigid. Newman, whose work I think is great, and Rothko are not characteristically Expressionist.

BH: They include themselves.

DJ: And I don’t think there’s been any public reaction against them.

BH: Against Abstract Expressionism?

DJ: Well, against Newman and Rothko. They’ve been very influential with a lot of people my age. Usually when someone says a thing is too simple, they’re saying that certain familiar things aren’t there, and they’re seeing a couple maybe that are left, which they count as a couple, that’s all. But actually there may be those couple of things and several new things to which they aren’t paying attention. These may be quite complex.

At the moment, when someone says it’s too simple, they mean that it doesn’t have the composition that the Abstract Expressionist painting, or Cubist, or whatever — going back — had. It doesn’t have a lot of parts working against one another, a lot of colours working against one another. If it doesn’t have this, it’s simple to them. It may have other things which are really pretty complex. They may be read all at once. This is important to most of the best work going on now. It has to have a wholeness to it that previous work didn’t have.

BH: If you’re going to do a box, the line has to join at the right spot.

DJ: Yes. Boxes are pretty simple. The corners all have to join. Even in a box you have, after all, just on the top four edges. And there are four more down the side and four around the bottom. It really isn’t all that simple. And that’s just plain box. But one of mine has subdivisions in it — a trough is made of a lot of subdivisions. Well, those subdivisions are progressive, and the progression in there is really pretty complicated. It looks like a trough with a lot of arcs along it and it’s very simple if you don’t start to think about the progression and the number of arcs. But if you take that into consideration it’s reasonably complex.

Read more in Modern Matter issue 14, The Mother Issue.

“The work isn’t the point; the piece is.”