To The Serpentine

4.07.19 | Article by Michele Robecchi | Art, interview, Magazine | MM8 Click to buy

An interview with Julia Peyton Jones marking the fifteenth year of The Serpentine Pavilion

Photography by Jukka Ovaskainen

Michele Robecchi: 2015 is the fifteen anniversary of the Serpentine Pavilion. I remember the first one was Zaha Hadid’s. Wasn’t it originally commissioned for one night only?

Julia Peyton-Jones: It was one of the great miracles that it stayed longer than one night. It started the whole ball rolling in a way that we couldn’t have possibly anticipated at the time. It is thanks to Chris Smith, who was Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, under whose jurisdiction The Royal Parks were located. He loved the structure Zaha designed, and he intervened with them, otherwise we would have never had a chance of keeping it up for longer. MR: How did the idea of a Pavilion dedicated to architecture come about in the first place?

JPJ: It was a sophisticated game and a challenge. We were going to do a gala on the occasion of our thirtieth Anniversary in 2000, and I wanted us to do something that was different from everything we have done before. We went to see Zaha Hadid, she accepted the commission of doing a temporary structure, and we started working on it. Once Chris’ intervention enabled us to keep the structure up for longer, we installed a café, and the genesis of our annual architecture commission, the Pavilion, was born. What was interesting about Zaha’s project was that she not only designed the structure — she also designed the furniture. It was a Gesamtkunstwerk

MR: How so?

JPJ: When I became Director in 1991, ‘Why is this art?’ was a regular question by the press. When the Princess of Wales became our patron in the early 1990s, people didn’t stop thinking it, but it became less acceptable to say it because she was such an iconic figure. The Serpentine always stood for doing work that the general public was unfamiliar with, and I believe she did a very great deal to help with the sea change to contemporary culture in the UK. When she attended our gala dinners, we were doing exhibitions that were curated for one night, and we decided to extend that principle by commissioning Zaha Hadid to design a Pavilion in which the thirtieth anniversary Gala Dinner would be held and which would be in situ for 24 hours.

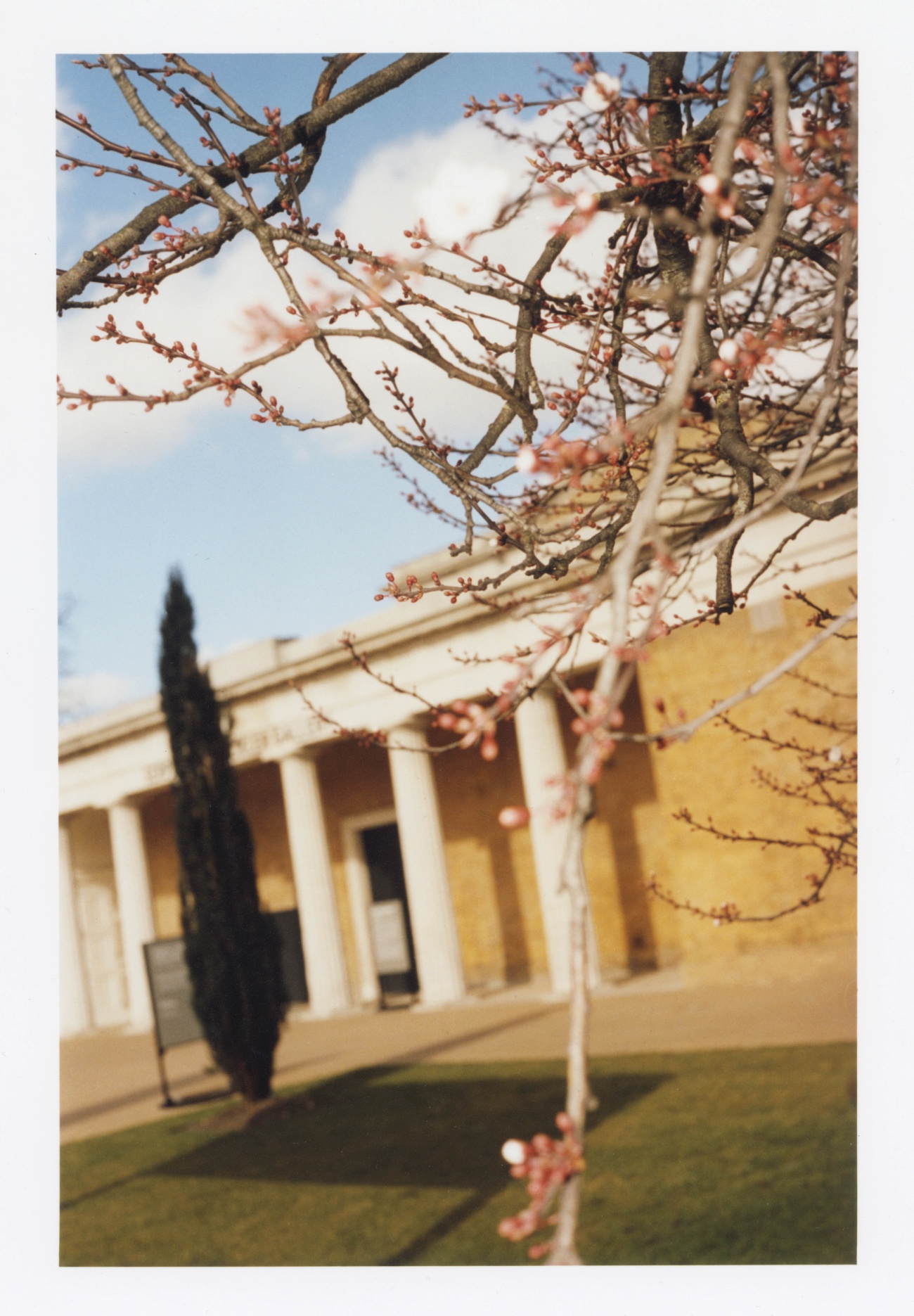

Serpentine Gallery, London (2015)

MR: When you became Director of the Serpentine, the YBA had just started. Do you think contemporary art was not necessarily better understood, but at least more popular by then?

JPJ: ‘Freeze ’ (1988) completely changed my thinking. I put the cultural shift down to that exhibition. It showed all of us working in institutions that there was another way to do things. ‘Broken English’ (1991) was the first show that I was responsible for programming on my arrival the the Serpentine Gallery and Damien Hirst and Jay Jopling had just began working together. It was a relatively small world that by no means had been fully embraced the public. The benefits to this country of that period was a flowering of visual awareness that couldn’t have possibly been predicted. It was unclear at the beginning whether the ground that we’d gained for culture was something that would continue or something that would disappear. ‘Freeze’ started it all.

Julian Peyton-Jones in her gallery office, 2015.

“I often see people coming to the Serpentine, looking through the door, and not coming in. They feel this sense of uncertainty and caution — even concern. That doesn’t exist with the Pavilion. From the minute the public can access it, they come in, they move the furniture around, they set it up, they are completely at home. They host dinner parties, they bring cutlery and candles, they treat it as if it’s their own, as if it’s been there forever. That’s really inspiring. At the same time, they learn about architecture and the work of an architect they may not be familiar with.”

JPJ: I think so. One of the things about the Serpentine is that it had a long, distinguished history that I was very fortunate to inherit. In the earliest days of this institution there were exhibitions by Jasper Johns, Giacometti and Wilhelm de Kooning as well as less established artists. The question I asked myself was, what way can the Serpentine contribute to the discussion? The Pavilion is very much part of that thinking. It gives us the opportunity to present the work of some of the greatest architects in the world as well as those who are lesser known.

MR: Is there a brief architects have to follow when they are invited?

JPJ: It is the same now in year fifteen as it was in year two –it is simple. It gives the architects maximum leeway to do what they want to do. The whole project is predicated on an artist’s commission, not an architect’s commission. In the early days I talked to the architects a lot about how the structure should represent their language, because it is an exhibition of architecture for the public and a way to have a better understanding of what they do, particularly as there are no buildings by the architect in England at the time of our invitation. The Pavilion has an important function as a café. I don’t believe it would have been so successful without giving people the opportunity to stay in the structure and not feeling either pressurised about just being in the space. It’s an important component.

MR: Many architects you work with subsequently received commissions in the UK. How much do you think the Pavilion is responsible for that?

JPJ: I hope the Pavilion contributes. The reason I say that is because not only is the project a leap of faith for everyone concerned, but also because the architects are incredibly generous to us. I always thought that by making people aware of their work, it would come back to them through commissions. It is our way of saying the investment you are making in this project will be returned to you. For example, Daniel Libeskind was commissioned to design a house in Connecticut based on the Eighteen Turns Pavilion he did here. It is an opportunity for architects to do something that allows them to dream because it doesn’t have the same restrictions as a permanent building, which has to include kitchens and bathrooms.

Read more on Modern Matter, Issue 8 – Photogenic