Höller & Parreno

Philippe Parreno and Carsten Höller have a long and storied history together, both as friends and as artistic collaborators. In this interview — conducted over numerous cigarettes at London’s Mondrian Hotel and overseen by this magazine’s Editor, Olu Odukoya — we learn that their decades-long dialogue first began in 1991, and is set to end in the founding of a retirement home for creatives (including, quite crucially, access to “a suitcase full of drugs”).

Photography by Jukka Ovaskainen

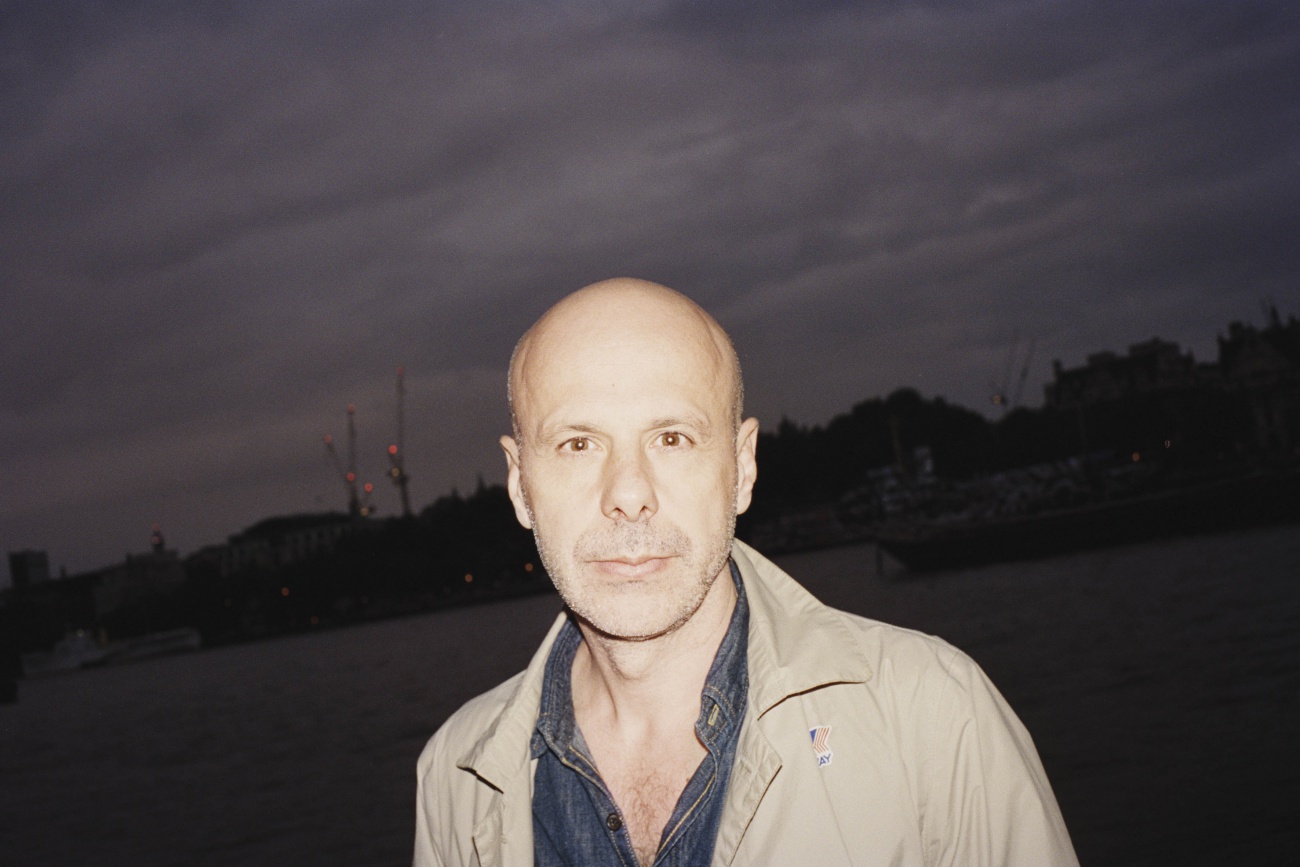

Carsten Höller

OO: You’ve previously mentioned that the two of you talk about “everything but art”…? ∆ PP: We discuss ideas, mainly. ∆ CH: …in 1991 we didn’t know each other at that time. Somebody told me that there was a guy in France who did a demonstration with children, and I had also done a demonstration with children. I remember I was in a group show at Air De Paris in Nice, and you were already working with them, and they put us in contact. Then I went to see you in your studio, and you showed me slides — ∆ PP: Huh — I don’t remember that. ∆ CH: — on a table, like a light-box: small slides. You don’t remember that? Really? ∆ PP: No. ∆ CH: [Disappointed] Ah! Well, it’s definitely right. ∆ PP: Are you sure? You made it up. ∆ CH: I did not! ∆ PP: As you can see, we have known each other for a while: we never really stopped talking, so it’s been a long conversation. We have a close friendship, but not in the sense that we go on vacation together; it’s more that we share a common grammar. If we meet every three months, we don’t really need a lot of time to catch up — all we really need is a few seconds and we’re back again, on the same conversation we were having three months ago. ∆ OO: When you visit each other’s shows, how do you respond to that experience? Do you review each other — do you ask questions? ∆ PP: I went to see Carsten’s Soma show in Berlin, at Hamburger Bahnhof, and I was really impressed by it. Just like today — I came on the last day of the show, to see the [Hayward] show with Carsten. I do recognise things which have our common grammar, yes. And I learn from it, of course. ∆ OO: Do other people notice that you have this ‘common grammar’ — does that come up?

PP: Yeah, definitely. We’ve certainly been more associated in the past than we are now, partly because we do fewer group shows. At one time, group shows were really a way of living for Carsten and I — spending time in different places, improvising, and coming up with stuff, and talking at length about it over dinner. We started to work like that a lot: spending time in an exhibition space while inventing strategies or scenarios. We weren’t really coming into the space with objects as much as we were negotiating being an artist. It was an open conversation. ∆ CH: We’ve been speaking about getting old together. I’m 53, and he’s three years younger, so ideally, in the future we would live together: and not just the two of us, but some other friends too. ∆ PP: A retiring house, you know? ∆ CH: So that’s something we have to fix now. ∆ PP: Carsten has been collecting drugs in the meantime, so we will have this suitcase, right, full of drugs? ∆ CH: Suicide methods… We need to collect these drugs, so that we have different ways of taking something if you want to explore or kill yourself. So that other people can help you to do this, instead of going to Switzerland. The last few days — the last few years — of your life: it’s the time that would be great to spend together. ∆ And we could also make this into some kind of profitable business: the idea would be that it is, at the same time, a clinic for people who want to stop taking drugs or have other problems. So they can come and hang out with us, because we kind of lived through that already. And we can make money at the same time, from rock stars and stuff; we’ll be getting entertained, but at the same time, we can show them a way to live. But still we have the suitcase, in case of need. Not just for the suicide. At the old age, we want to explore the real.

OO: In your shows, you both often work to a very large scale. ∆ PP: That’s recent, and it’s not about putting the big phallus up on the table — or if it is about that, I don’t want to know the psychological details. For me and for Carsten, I think — when I look at the Hayward for example — it’s all about creating a public space… ∆ CH: Public space in the sense of people gathering, and spending a common amount of time in the same space, and getting a unique experience. At least for me, the scale has a lot to do with the fact that I want to avoid — to a certain extent, at least — a situation where I’m showing something for people to contemplate. I want to be in the position where I’m producing a certain experience, instead; it’s an experience that’s peculiar to you, but it’s also specific, because you are reacting to something that produces that experience. And that often means it has to be big enough for you to get in — so it can’t just be a little thing that is meaningful in one way or another when it’s in my studio, it has to be something big enough that you can expose yourself to it. ∆ PP: The show I did at The Armory, that opened the same day that you had the show opening at the Hayward, was also something where I’d tried to come in with the idea of something like a public square where everything is completely open: I didn’t build any walls. So the challenge for me was how other people spend time in a space, among each other, looking at each other, and looking at each other looking at something. And the same thing happened at the Hayward, where you get this idea of hanging around, and gathering with others. So the feeling was quite similar.

OO: When I went to the Hayward, I definitely felt that it was more about the people — that you were doing it for the people who were there, rather than for the sake of the gallery itself. ∆ PP: I think there’s a big semantic difference between an audience and a public. My work is not about things. I, certainly, don’t have any subjects in my work, as much as it is an exploration of how a form appears in space and time. The same thing happened with Carsten. So it’s all about that — how do you bring things up, so that the public can come around and participate in that kind of environment, rather than show a display of objects? It’s more about producing some kind of experience, slightly collectivist — ∆ OO: Like life, you mean? ∆ PP: When you go to a museum, you choose the length of time you that you want to spend in front of a painting. Cinema is much more collectivist, because you go, and it’s a dark room, and you all are together enjoying the same thing at the same time. We are in-between both. It’s a collective experience, and still quite an individualistic one, where people find themselves in synchronicity. ∆ OO: Something I’ve noticed from hearing you both talk, and in what you said earlier: you don’t necessarily separate talking about your life from talking about art. I thought maybe that your work is more about everyday life, in a way — which is something that, publically, people are able to understand more, or participate with more. Is this a different experience than when you’re making something with the art-world in mind? Because you’re always ‘in’ already — you’re already doing your exhibitions in these very ‘art’ places, but you always seem to be looking out instead of in. ∆ CH: For me, a big inspiration was the fact that I grew up in Belgium, and my father really liked Breugel, and I did too. I found it fascinating to see this scenery where you have plenty of different people doing plenty of different things; like in all the winter landscapes where there are a lot of different activities going on. So as both Philippe and I said, we wanted to get away from showing objects that are meaningful, in one way or another, and a way to do this is to create a scene where you are part of the exhibition — because you are being looked at, but also you look at the other people doing these things, and in this way it becomes a public space, and you can even, possibly, produce some kind of mass phenomenon, like a mass hysteria. I’m always interested in the idea of madness, or of a way out of the ordinary; a way out of utilitarian thinking, which is the predominant way of keeping things under control. And in producing public spaces where you can experience together something unique, out of the ordinary, even mad. Something that is not even confined by words anymore — we end up talking about things that are, ultimately, very hard to define.

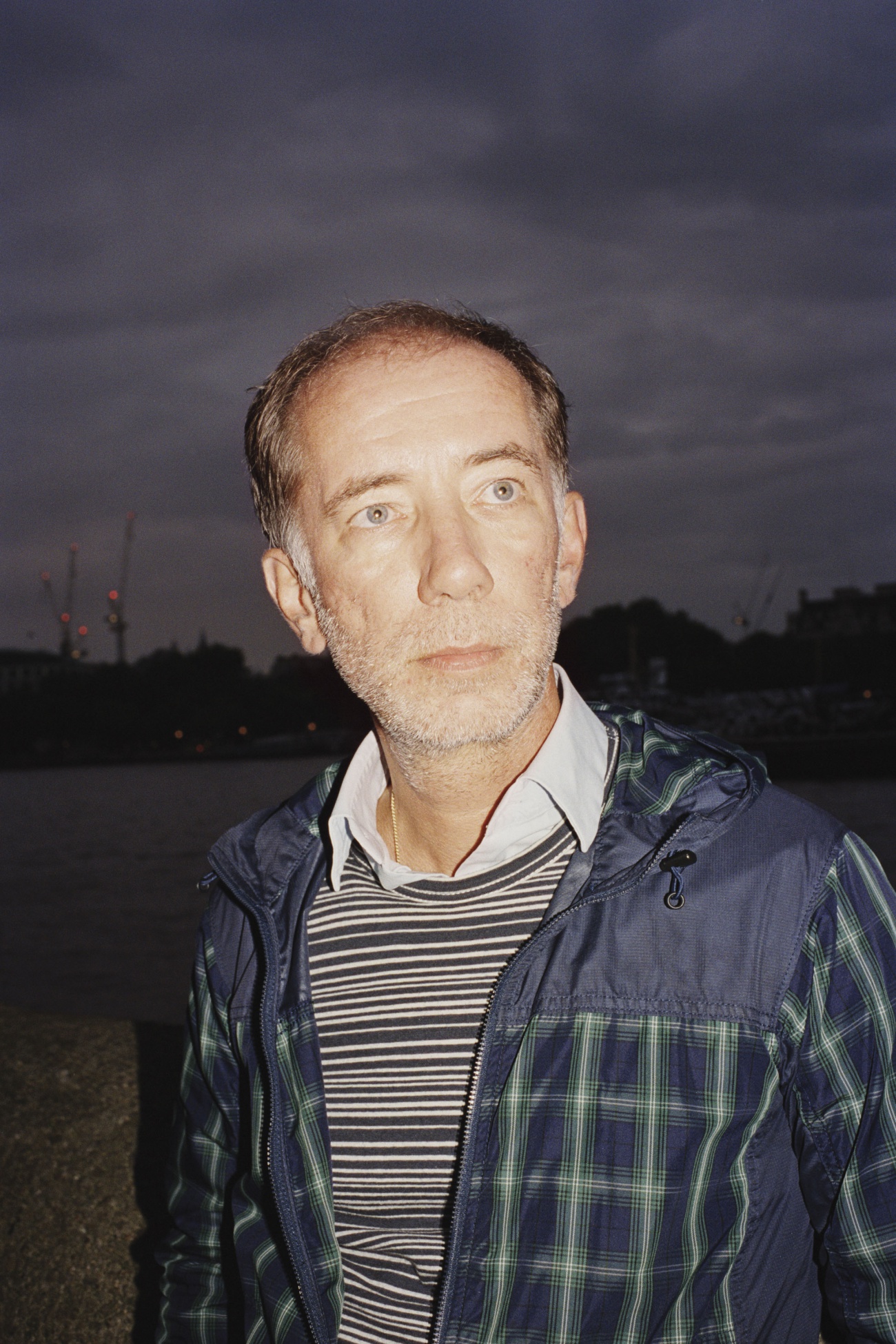

Philippe Parreno

“My work is not about things. I, certainly, don’t have any subjects in my work, as much as it is an exploration of how a form appears in space and time.”

– Philippe Parreno

PP: When you say mad, you mean that the logic is not apparent? It’s against logic? ∆ CH: It’s another logic, that is provided there to be used. And people use it in different ways. Children just have fun, and some adults have fun too; others are reflective. So there is the possibility of creating platforms in the exhibition — almost like stratifications, without being hierarchical, but providing the opportunity for different models of behaviour at the same time and place. And suddenly, it becomes a whole. ∆ OO: The more the audience loses themselves while experiencing an art show, the more the art does for them? ∆ PP: It’s all about engaging in time, and forgetting yourself a little. ∆ CH: And at the Hayward, people got really crazy! In places where we didn’t expect. We had to put all these barriers, and put in more guards, and get it under control. But I think, at least in these last weeks of the show, when it’s going to be taken down, that really they should leave it as it is, and let people just go for it, and do whatever they like, and see where things are going. It could become like an experiment, in a public place, where the end is unknown. ∆ OO: In my experience, people were forgetting that they were in ‘an art show’ — probably the best reviews of it you could get would be from people who had just come out, using the slides, into a public space again. ∆ PP: Maybe it’s a way to create new rituals, moving away from the eighteenth-century type of ritual of the art scene and art scenery. We keep trying to be experimental, and these conversations we’ve been having for a long time is all about that. ∆ CH: Well, we have one thing that we have been speaking about which is a common link between us, and that’s this idea of an amusement park. Which is something that we do, obviously, with shows like this: we are basically entertainers. But we had this particular idea of doing an amusement park that is not comparable to any you’ve ever seen…

PP: We called it Reality Park, right? ∆ CH: Yes, and the entrance could even be an anonymous door somewhere in a supermarket. ∆ PP: We made that Park proposal in Dakar. ∆ OO: There’s this connection with Africa with you, [Carsten]. I was a little surprised — I actually thought, he does African better than me! ∆ CH: Well, my first trip to sub-Sahelian Africa was in 1995, when I went to Benin to visit a friend. It’s very hard to explain: it’s a fascination, and there is no explicable reason for it. I have other fascinations too — I’m fascinated by birds, for example, and I can’t explain why I have that, either, it’s just there. And it’s not Africa itself, I have to say, as much as it is special places there. I’m very interested in Congolese music — since I found it, I find I can’t listen to other music anymore. It’s getting to be an obsession, or something. It’s not really unconscious — I’m conscious about it — but it’s not really something I’m directing, either. I feel something is directing me, and I’m more than happy to follow.

OO: I’m about to go to Africa — to Senegal — for the first time in maybe twenty years. I’m from Lagos in Nigeria, which has a different kind of vibe. ∆ CH: Have you been to the [New Afrika] Shrine? ∆ OO: Yes: my mother was actually in the same class as Fela Kuti at school. ∆ CH: These are the kinds of places that I think have a link to the art shows that Philippe and I are talking about. The Shrine is the third incarnation already — it has burned down, it has moved. You go in there, it’s basically a music place, but you know right away that the rules that normally apply to society don’t work here anymore. And it’s not just for one evening — even when there’s no music playing, there’s a common spirit of being in a society within a society. ∆ OO: And Africa is very public. That’s why I think it’s interesting. Like the first night that Fela Kuti did — he would play, and he would talk to the audience, and you could tell him if what he did in his last record was rubbish, and he would tell you his own opinions. This is how he would get all the political conversations that he would need for his records. And that’s a very, very African thing. ∆ CH: I’ve seen this also with one of the guys we made the film Fara Fara with, Werrason, last time I was in Kinshasa. He was about to go into the studio to record a new album, and he was playing two versions of a song to the public at a so-called ‘rehearsal’ — actually, it was a concert with several hundred people, and he was asking them which one they thought was better. He was the only musician I ever saw who was trying to cool down the public, because they were arguing like crazy. ∆ OO: Since your work always deals with the public, do you judge its success on how they react to it? ∆ PP: I was saying this to Carsten: for the last show in New York I went back after the opening and I spent about three weeks in the space, every day and I really enjoyed it. People came and sat down with me and talked; it was really great, because it was just a normal conversation with people saying “hey, you know, what do you think?”, and it was not the opening, you know? It was just a regular day. And I was thinking that if we do this, we’re kind of inverting the usual protocol. It becomes again, to resume our earlier conversation, a studio practice. In the morning I was recording new elements and injecting them back into the space, so it became a place of production. And we both come from that — the idea that the exhibition space is a place to produce art, and not just to show art.

OO: I heard a lot of wonderful things about your show at the Palais de Tokyo. I understand you did something very interesting with music there? ∆ PP: It started with the fact that in order to organise all these events in the space, instead of having a time code which is essentially a white noise to hang the moments in, a timeline that structures the show, I used a piano piece. So the piano piece was key as a regulator. We have already talked about logic, and mad logic — there was logic behind the show, which was hidden, but which I followed methodically to the end. So the show was run by a movement of Stravinsky from Pétrouchka which was totally arbitrary, but it worked. It’s also because sound can attract your attention in a sort of non-authoritarian way. You hear something moving, and you are attracted by it. And then you see somebody before you, already there, so to go back to the public: the one who is before you in time knows a bit more than you. Classically, if you were about to see a film, the guy in front of you, you want to chop off his head, because you can’t read the subtitles; there, in an exhibition space, the person before you knows more than you. So it’s a totally different kind of relationship that you have with the other.

Carsten Höller

“We had this particular idea of doing an amusement park that is not comparable to any you’ve ever seen…”

– Philippe Parreno

Read more on Modern Matter, Issue 9 – Everything Has Beauty