The Boiled in Between: In Conversation with Helen Marten

English artist Helen Marten uses an internal, cryptic logic to unpick the binary relationship between question and answer. She then wads it with simulacra, showing the riddled possibilities of the endless associations between A and B, or even C and D and E. Ordinarily, she has done this through her sculptural and installation works. Through The Boiled in Between, however, Marten’s first work of fiction, the artist enmeshes her chaotic depictions of humanity into an abstract wordscape that floats and falls and gushes with observational intensity.

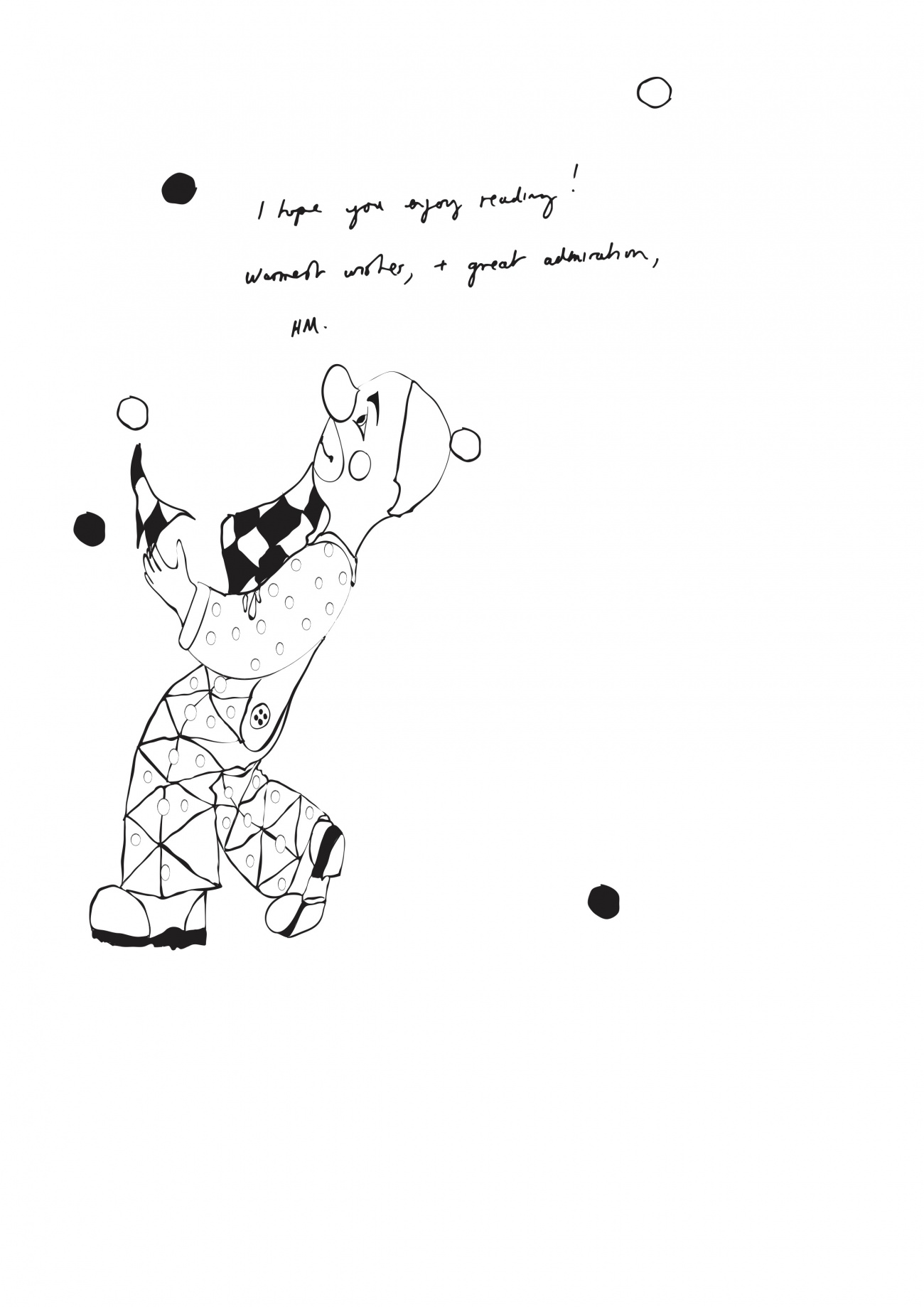

With Modern Matter, the artist discusses this new extension of her practice, presented here alongside a selection of artworks inspired by the book – from Marten’s most recent show at Sadie Coles HQ, London – and an extract from the book itself.

All images, Untitled, are from 2020, copyright of Helen Marten, courtesy of Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photography: Robert Glowacki.

Mazzy-Mae Green: In The Boiled in Between, you read the absurdities of humanity in flecks of dislodged earth and dirt-gashed shirts. Do you feel this is the most pertinent way to interpret our existence?

Helen Marten: I suppose in immodest failure the world survives, and it might be as simple as saying that this kind of noise is the rhythm that structures all bigger ideas. I do believe that provisional absurdities can provide deeply profound interpretation. Of course there is politics in everything – the sonic density of history and all its semantics, its objects, its matter – it folds and survives in the smallest flecks. These bigger cultural concepts – identity, economy, survival – are simply packaging for billions of smaller fractured events. Even dirt: the horizons of soil are huge! It is saturated with potential signification. Maybe I’m interested in these expulsing gestures in the same way as some people might watch the World Cup as an exercise in an expanded ‘cultural studies.’ Something like an archive of melancholy or a pre-modern sensitivity that is political without being Politics, capital P.

MG: The characters seem always to be falling. Is there something about a person in descent that is inherently more interesting?

HM: This links quite specifically to your first question – to positions of precarity. To be off-balance or ever en route necessarily forces a reclamation or re-articulation of a body’s relationship to the earth, to gravity, to itself. A character falling poses a paradox, a confusion of figure and field: falling as controlled comedic clatter or falling as unspooling psychological health. To trip up is to notice something. To fall down is to forcefully reconnect, get damaged or break. Or to mend and shrug off the blood in continuation. And if we’re thinking about descent, of course a downward plummet always has more velocity! Atoms that collide at speed tend towards transformation, and how exciting is that?!

‘A character falling poses a paradox, a confusion of figure and field…’

MG: In the text, you oscillate between body, food and home, and between beauty, sex and disgust. As the story progresses, these areas seem to meld. Where are the lines between them?

HM: My feeling with all these things is that perhaps there is no line. Imagine people as points of civic ordinance all mostly existing within an envelope structure of ethical morality. People operating algorithmically: exchanging, living, dying, fucking, breathing, labouring. Then equip them with libidinal language and an ongoing system of wounding (poverty, illness, violence, etc.) – suddenly figuration is in everything so profoundly and intractably. Even garbage is alluring because it informs us of human systems. Think how quickly something monkish becomes pornographic by association. I feel a mutual devotion and disgust to all of these categories, but one fundamentally powered by an obsession with their abundantly shared incongruities. None are ever what they first seem and all have the power to possess with totality.

MG: On page 104, you write: ‘Ethan held a pistol once and felt how irrelevant true or false was in the pursuit of knowledge.’ Why is that so?

HM: Ethan is a committed nihilist. Perhaps he is also something of a clown who rejects the morose logician, who rejects the idea that the rigid alternatives of ‘true’ and ‘false’ are relevant to the pursuit of knowledge, to life or death, or the philosophical wormhole of trying to understand a binary action with a binary answer! In short, perhaps Ethan recognises through all his relentless performance of misery and ridicule, that multiplicity is essential to understanding, that the form of words symbolises an indefinite number of diverse propositions.

MG: Contrary to your other characters, which appear to be embroiled in the mess – implicated – The Messrs. sit above the story, looking down. Who are they?

HM: As the Messrs. themselves suggest, they are instruments of psychic observation. I suppose they are something of all people – an audience, constructed always and forever by whomever and whenever, by time and spirit. I know that sounds impossibly enigmatic – a riddle! – but what I mean is that their presence is designed to be a simultaneity: as omnipotent as the cosmos and as evidence, more and more, that simplicity doesn’t exist. They are so many things: amazed conspirators; egos adjusted; staggering ghosts; feelings; admonishments. They are in and of many of the things they discuss: wind, weather, animal, blood. They are always changing. Perhaps they might even be akin to chemical stimulant, something like the way caffeine rips you out of yourself and carries your pulse off darting in thousands of angles of pursuit and commitment!

‘The world is impossibly fat and full of information. And stupid images can be absolute. So between those two poles, there is an enormous amount of scope for reflexive play.’

MG: You begin in a heightened conceptual place, writing through a wider lens, before narrowing the story. What is this effect in your work?

HM: When I first started writing the book, I had emerged from a madly busy period of making exhibitions and I was frustrated with the conventional retinal way of looking at things: eyes-forward-straight-ahead-right-now. I wanted to brutally twist that, not make a space of indeterminate collage, but really wring material process, image digestion and language intent into something else. Perhaps mostly for myself to short-circuit and start afresh. I can’t help but see concept or metaphor in most things. The world is impossibly fat and full of information. And stupid images can be absolute. So between those two poles, there is an enormous amount of scope for reflexive play.

MG: The linguistic rhythm of the book is like dreamwork: the words are soft and elegant, distorting the frictions and unpleasantness experienced by the protagonists. While you were writing, did you think first of language or plot?

HM: It will sound maddening, but I try to think with whatever the ambient tone for the day is! So always movement, clogged or facilitated by language, always a vehicle of sorts, and always plot but perhaps not always conventionally surfaced. They’re all like their own micro-surfaces that give and receive, are improvised, unmoored. If you were to conceptualise the impulses of this book, one way might be to imagine language and plot like furious animated heads engaged in the continual process of trying to drown one another, surfacing and drowning on terrible repeat.

MG: What was the process of creating a work like this?

HM: I sat at a desk every day for about a year and when things didn’t pour out, I opened other books and used their words like lakes to swim in. Like dominoes. It was a deeply pleasurable process of translation, bouncing back and forth between all the things I might claim to know about image and all those I might claim to know about language.

The Boiled in Between is published by Prototype.