Paulina Olowska : Destroyed Woman, discussion with Michal Wisniewski

20.02.20 | Article by Alex Bennett | Art, culture, interview | MM17 Click to buy

Paulina Olowska filters symbolism with dexterity: mythology, socialism, consumerism, design, fashion and leisure coalesce in her paintings, drawings and collages. At times they’re coloured by the semiotics of surrealism; at others they are oblique reviews of nostalgic consumer culture. Creating alternative futures and pasts, Olowska decomposes modernism, and jerry rigs it into new life. In the following conversation, Olowska elaborates on her work with fashion designer Michal Wisniewski, where the duo renewed a set of decomposing garments recently unearthed in the garden of Olowska’s studio and communal retreat at Villa Kadenowka in Eastern Poland.

ALEX BENNETT : For one section of Destroyed Woman at Simon Lee Gallery, you collaborated on a series of sculptures based around Michal’s dresses. Perhaps we can start by addressing Michal’s practice and approach to textile design. Can you tell me about the background to these garments — how they were created, and their context — and your approach to fashion design more broadly?

MICHAL WISNIEWSKI : Usually, a piece of fashion must be functional; it must have the purpose of clothing someone, and being worn. However, in this case I was able to discharge the functional element from my pieces, and let them be works of art. They served a purely narrative role. We buried the fabric in the garden of Kadenówka. We also buried several items with these fabrics, including eggs, bones, and photos. The idea was to find a way for the fabrics to become immersed in and absorb the stories of the location. The irony is that after 3 months of being buried, most of the fabrics had disappeared — they had been eaten, or decomposed. Because the concept was supposed to fit the theme of a “destroyed woman,” I was inspired by the house robes worn by women in Communist Poland. It was the initial reference for the shape of the dresses. With the help of Halina, an amazing seamstress that Paulina found, the dresses were sewn within just a few days in Kadenówka. They were pure experimentation: mainly draped on a mannequin, or put together using free hand pattern cutting.

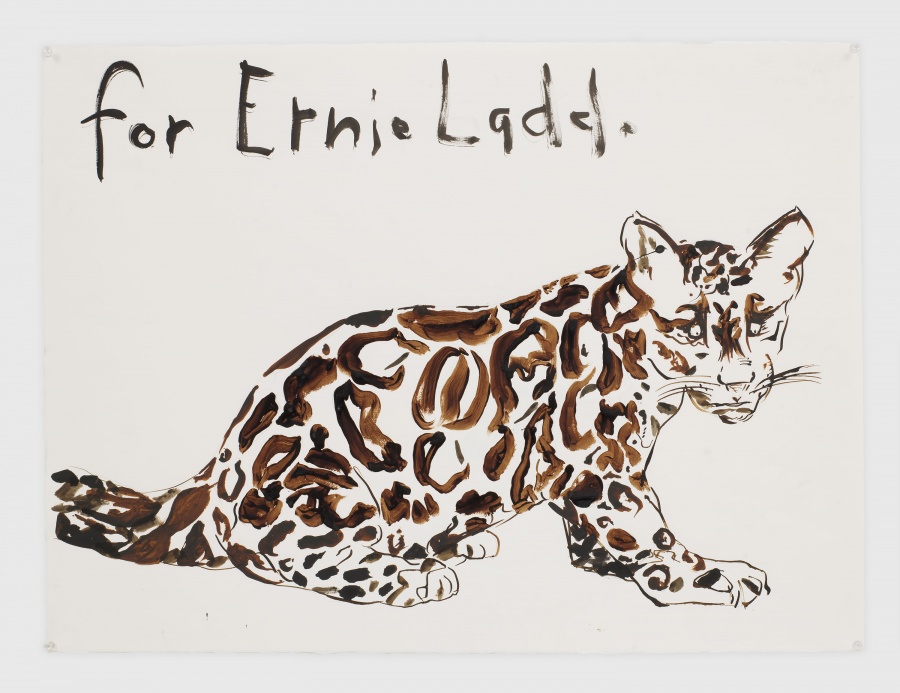

Paulina Olowska, Monologue, 2019 | Oil on canvas | Courtesy of Simon Lee Gallery

AB Paulina, you share an interest in textiles and fashion editorial across American and Eastern European culture. Some of your paintings appear to directly reference editorial and fashion campaigns with a touch of nostalgia, while others are far more symbolic. In either case, an individual figure is often presented with a very particular style. How do you come to include fashion within a painting; is it geared toward the portrayal of an individual, if occasionally mythological, character?

PO In the beginning, I was using very specific source material like Te i a (You and Me), an old Polish magazine — instead of using models, the photographer would just ask real women to pose, to show the so called ‘fashion’ of that time. From here, it became a representation of where I was, and of that stage in my life. I tend to fantasise about the women I will paint, and in that way, they become my muse. I visit a certain archive to flip through magazines, and to be inspired. Some of the women I paint can be recognised, others are unknown. For Destroyed Woman I tried to use my own photographs of real women I have seen in my life. Now, I realise I am trying to depict women who embody a specific or strong virtue — one that they that might talk or persuade the viewer into seeing, so that he or she believes she has a secret knowledge.

AB How did you two both come to collaborate for Destroyed Woman? Had you worked together before?

PO I was invited by Vogue Polska to create their first ever Art Issue, published November 2018. It was during this time that I connected with Michal and we have remained in close contact since.

MW When Paulina was working on the art issue of Vogue Polska, she used some of my pieces from my undergrad collection in her photoshoot. That was the beginning of our relationship. We emailed each other frequently, but the funny thing is that we didn’t meet until we were both in London. Paulina invited me to collaborate with her, and I was absolutely thrilled. It was great opportunity! I just graduated from MA Fashion at CSM the previous March. Not a lot of young designers have the chance to work on such big art projects.

“I tend to fantasise about the women I will paint, they become my muse.”

AB Given your collaboration, I’m wondering if you both share an affinity for the narrative quality of textiles, as well as the vulnerability and fragility of fabric itself. Are you interested in the storytelling potential of clothing — and what do you think are the similarities and differences between your respective practices?

PO I think between our practices there are similarities. With my work I tell stories, and I see this quality in Michal’s work too.

MW My work is usually very textile-oriented. I think that fabrication is crucial for making interesting garments. I appreciate working with the residents from Post-Communist countries. For my undergraduate degree, I collaborated with a retired lady who was a silk painter in the 1980s, in Milanowek, Poland. In my fashion work, I really want to transform and interpret traditional craftsmanship into something modern. It’s very relevant for contemporary fashion, especially now that a lot of crafts are like endangered species.

AB Paulina, you transformed Villa Kadenowka, a 1930s villa in Rabka, Eastern Poland, into space for artist’s events. The space has a very rural, quiet setting. What motivated you to create a communal space in such a location?

PO I wanted to make a space for women, for artists, for learning, and for culture.

AB The fabrics for Michal’s dresses were buried in the garden of Villa Kadenowka; these were later placed on show, with each mannequin in the exhibition adorned with a ceramic house, as though coupling the subject with a specific architectural environment. What encouraged this approach to burying and unearthing these dresses?

PO Our idea behind burying the fabric was the result of a combination of different thoughts. Kadenowka has its own history — both the house, and its surroundings. The fabrics were buried in the garden on the site of the old swimming pool. Digging through the ground is like digging through history, or digging through the house. And the dress is very connected to the woman; to the idea of living in the house. So, the ceramic house became the head of the woman, and the robe became the body. The houses were made for past exhibitions, so in a way I was investigating my own history while quoting art history. I was thinking about Louise Bourgeois’ Femme-maison, and some illustrations I found from the 1960s.

Patchwork Seamstress in Unknown Dwelling, 2019

Corpse Bride, 2019

AB Paulina, this isn’t the first time you have worked with a performative approach. I’m thinking of performances such as Slavic Goddesses—A Wreath of Ceremonies, at The Kitchen in New York, where you revisit the work of multidisciplinary artist Zofia Stryjeńsk and her understanding of ballet as a ‘wreath of ceremonies’. Can you tell me about this work, and how you approached the production of the costumes here?

PO The costumes were based Zofia Stryjeńska’s drawings of Slavic deities from 1918. These goddesses came to her in a dream, and my designs were based on six of the drawings she made.

For the performance at the Kitchen, I collaborated with choreographer Katy Pyle to create a suite of solo dances.

AB In light of Simone de Beauvoir’s 1967 book of short stories, The Woman Destroyed, do you see destruction as a site of potential for subjectivity?

PO When I was re-reading the narratives of Simone de Beauvoir, it struck me how visual they are, I could see these women. De Beauvoir captured the idea of time passing; the women reflecting on their childhoods, their ages, their hair and skin, their bodies. For Destroyed Woman, I wanted to make space for these vulnerabilities, and to include them in my representation of the female experience. Although ‘destroyed’ is not a positive word to associate with womanhood today, I wanted to recognise that we are not always strong, powerful or successful; and that we are all capable of self-destruction.