If You Censor Yourself, You’re Fucked : An Interview with Larry Clark

20.02.20 | Article by Adam Zhu | interview | MM17 Click to buy

Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1943, Larry Clark is a photographer and filmmaker best known for his depictions of teen subcultures, drug users, and the 1990s skate scene. His first feature, Kids, was released in 1995, to both critical fanfare and media controversy. His first book of photography, Tulsa (1971), is widely considered to be one of the twentieth century’s most significant documentations of suburban drug use. Gus Van Sant and Martin Scorsese have both claimed to have been influenced by his early photographic work.

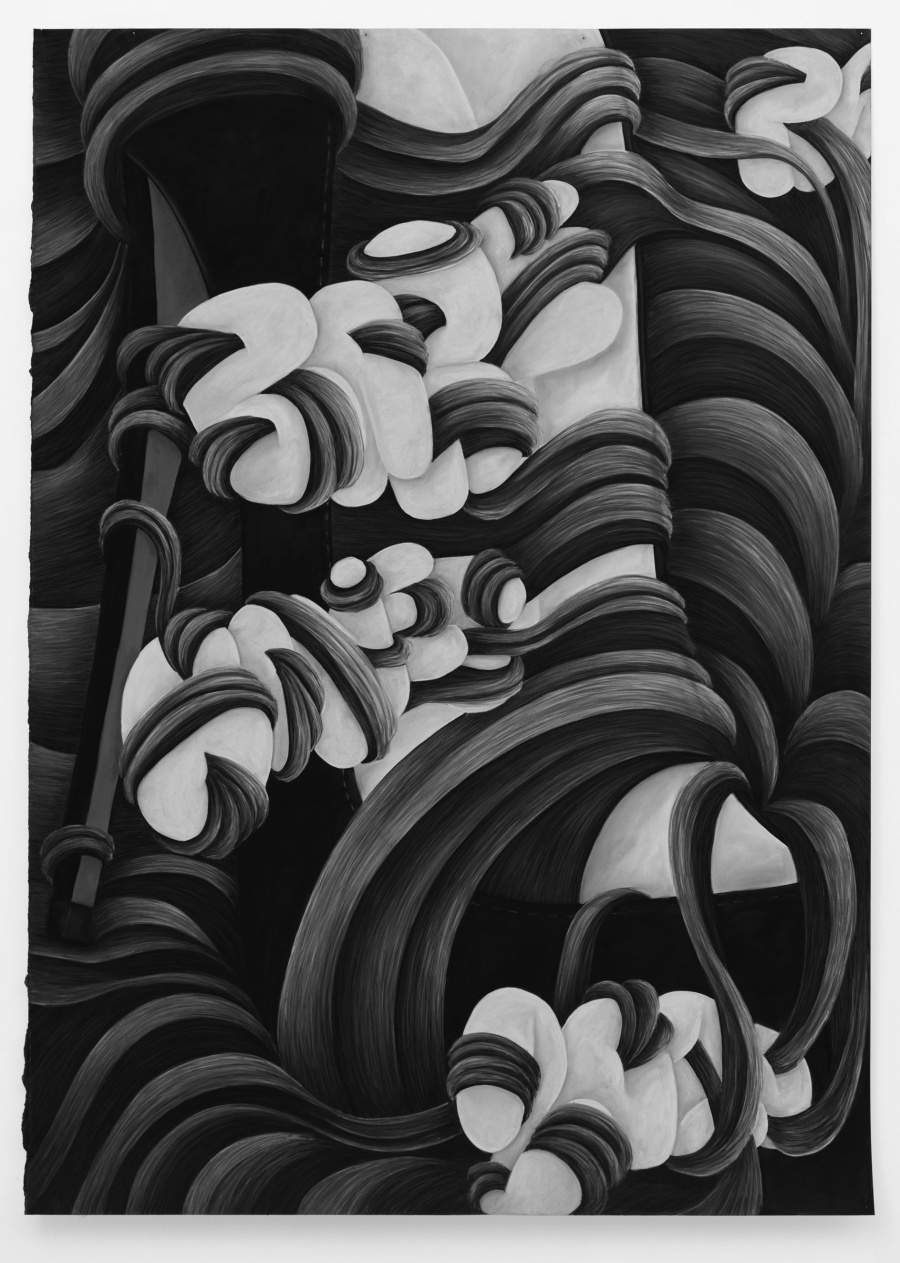

Larry Clark photographed in New York City by Peter Sutherland for Modern Matter

ADAM ZHU :

What got you into photography and documentation ?

LARRY CLARK :

My mother photographed babies. Back then, it was called “kidnapping” — you would go door to door, you’d look for clothes lines with diapers or baby clothes on them, and you’d knock on the door and talk your way in, and then photograph them in the home, and go back a week later and sell them. So my mother did that. And when I was about fourteen or fifteen years old, she had me doing it.

AZ :

Wow. So you started out…photographing babies ?

LC :

Babies, yeah. [Chuckles]

AZ :

Have you ever shown those photos ?

LC :

I showed them in France, yeah, a few of them.

AZ :

So when did you come to New York City? Did you go to school?

LC :

I went to school, yeah, in Oklahoma. When I was eighteen, I left home, as soon as I could. Because I was shooting amphetamines and I was really fucked up, and I knew I had to get out of Tulsa. So I went to Milwaukee for two years, to a photography school in the basement of an art school. And I hung out with the artists there, and I decided to start making photographs of my own, and expressing myself.

AZ :

What do you think drew you to these themes of youth and subculture, and things that some people consider taboo?

LC :

Well I was a kid, and I was doing that. So I was just photographing this secret life, with no ambition at all to ever publish it. It never entered my mind to make a book with a publisher, or anything like that — I was just practicing my photography. I ended up photographing my friends for ten years, and then I put it all together, and saw what I had. That’s the Tulsa book.

AZ :

It feels like there’s always a certain level of intimacy between you and the subjects. How do you feel about that relationship?

LC :

Well, they were my friends.

AZ :

As you grew to be a better-known photographer, did you find it harder to get into those situations to take photographs? Do you feel like you always have to be friends with your subjects?

LC :

It’s turned out that way. I’ve always photographed small groups of people that you wouldn’t know about otherwise. So if I hadn’t done it, you wouldn’t know about it. I never did it for commercial purposes, at all.

AZ :

How were you introduced to the figures from the skate scene that starred in Kids?

LC :

Well, I’d done autobiographical stuff all my life, and I was sick of that. So I looked around at kids, and I felt the most exciting ones visually were the skateboarders. I had some friends who were skateboarders. Tobin Yelland, who is now a photographer — he was a skateboarder then. So I started working with him. He came to a workshop I did one time, and I told him what he should do. Because he was making all these dumb photographs of these kids skating. And I said, man, you should spend time with these kids, and photograph what they do. But I’d already photographed teenagers — that was my fuckin’ book. So I just stayed in the game.

AZ :

And who were some of the first people you met? I actually work with Jeff, he’s my boss — so it’s funny. I work with some of these people you shot when they were younger. What was that relationship like, starting from a subculture you were in, and then moving on to another one?

LC :

I was in San Francisco, and then New York, and I started hanging out at Washington Square Park, and photographing skaters. I actually learned how to skate at forty years old, so that was kind of nuts. I hurt myself a lot! But you can’t photograph skaters and run after them, you have to skate. Actually, how old was I when I started to skate? Maybe I was forty-seven. Old! I was old.

AZ :

And they were probably, what, in their teens? Their twenties?

LC :

Yeah. But I had this idea that I wanted to make a film, and I wanted to make a film about kids. And I didn’t want to make a film about myself at all. So I started hanging out with these skateboarders through Tobin — I met a ton of them through him.

AZ :

And you served in the army, is that true? You went to

Vietnam?

LC :

I was drafted, yes.

AZ :

What year was that?

LC :

Jesus Christ…’64, I was drafted. So I was there early. It was much safer then. But still, there was a lot of shooting.

AZ :

You mention that you didn’t start documenting with a view to publishing anything. How do you deal with people’s reactions to things that a lot of people find shocking — the drugs and the sex portrayed in your images, or your films?

LC :

Well, it was never done to shock or anything, it was done because it’s part of life. So that’s what I would say. You know, there’s nothing that can’t be photographed, I don’t think, if it’s part of life.

AZ :

What was the experience of filming some of your other films like — Bully, for example, where did you meet that cast?

LC :

It was in Florida, and it was shot in the place where it actually happened. This little old town called Hollywood, Florida, which is right next to Fort Lauderdale.

AZ :

Because it’s a real story, right?

LC :

Yeah, it’s a real story. There was a book by a guy called James Schutze, who documented it in the first place. He had access to the lawyers, and the lawyers somehow had tape of these kids talking — so all the dialogue in the film is from the book. It’s all true, there’s nothing invented. It was a crazy film to make.

AZ :

So was that a real group of friends in that movie? How do you think about casting in general?

LC :

I had casting calls for that film. It was very difficult to cast and very difficult to shoot, because they were all kids. They were actors, and they had all been actors since they were ten or twelve years old, but still, they were teenagers. A lot of drugs and alcohol and problems involved there.

AZ :

But a lot of the actors in Kids weren’t actually actors? They were essentially playing themselves?

LC :

Well, some were and some weren’t. It was my first film, too, so I really had to direct them — I had to learn as they learned, and make them stick to the script. No improv. But I was very, very happy with that film.

AZ :

It must have been a tough group of kids to wrangle.

LC :

Oh yeah, it was.

AZ :

Do you stay in touch with the cast?

LC :

I see Leo Fitzpatrick.

AZ :

Yeah, I see Leo too. He works for Supreme now.

LC :

He’s very cool! A very smart guy.

AZ :

So what are you working on at the moment?

LC :

I was just in Paris, shooting a short film — probably twelve minutes — with a friend of mine who was in two of my films, Jonathan Velasquez. We just made a short film that we’re editing now. And I’m trying to write a new script, so I can make a new film. But as I get older it gets harder and harder to do. It takes so much energy.

AZ :

What was it like working with Harmony Korine? Do you work with him now at all?

LC :

I don’t work with him now, no. But when we did Kids, it was okay. He wrote a great script for me — my story, his script. I needed someone who knew kid-speak. He was great with that.

AZ :

If you look back, what’s the high point of your career for you?

LC :

My whole career? They’re all high points, I think. You go from this one to the next one, to the next one, and try to have fun. It’s all been good. But hard; making a film is the hardest thing you can do.

AZ :

Yeah, if someone makes one I’m amazed, and if someone makes a good one I’m even more amazed.

LC :

Oh yeah. Just to make a film is a miracle.

AZ :

So what’s your experience like working with brands? I know you’ve worked with Supreme.

LC :

It’s been fun. I don’t do it often. Supreme and Dior, and that’s pretty much it. I’ve known James [Jebbia] since 1994, so we’re old pals. If he asks me to do something, I just say yes, because he’s a good buy.

AZ :

Do you have any advice for young, upcoming filmmakers or photographers?

LC :

I guess be true to yourself, don’t censor yourself. Because if you censor yourself, you’re fucked — you’re losing a lot. Being an artist, censoring myself never came up, because it wasn’t something I thought about doing. And if anyone else wanted to censor me, I said no.

“You know, there’s nothing that can’t be photographed,

I don’t think, if it’s part of life.”