ICA, The Mall, London

In June of this year, the performance artist Eddie Peake followed Oscar Murillo, Tracey Emin, Bob and Roberta Smith and Subodh Gupta in organising an evening of performance and music for the ICA’s 2014 Gala — one of the most important events in the British art calendar, and an integral part of the Institute’s artist support-system. Ahead of the event, Modern Matter chaired a discussion between Peake and the gallery’s Director, Gregor Muir, who interviews him here about his practice, his personal history and his record collection — crucial environmental and personal factors which led to the realisation of the 2014 Gala performance.

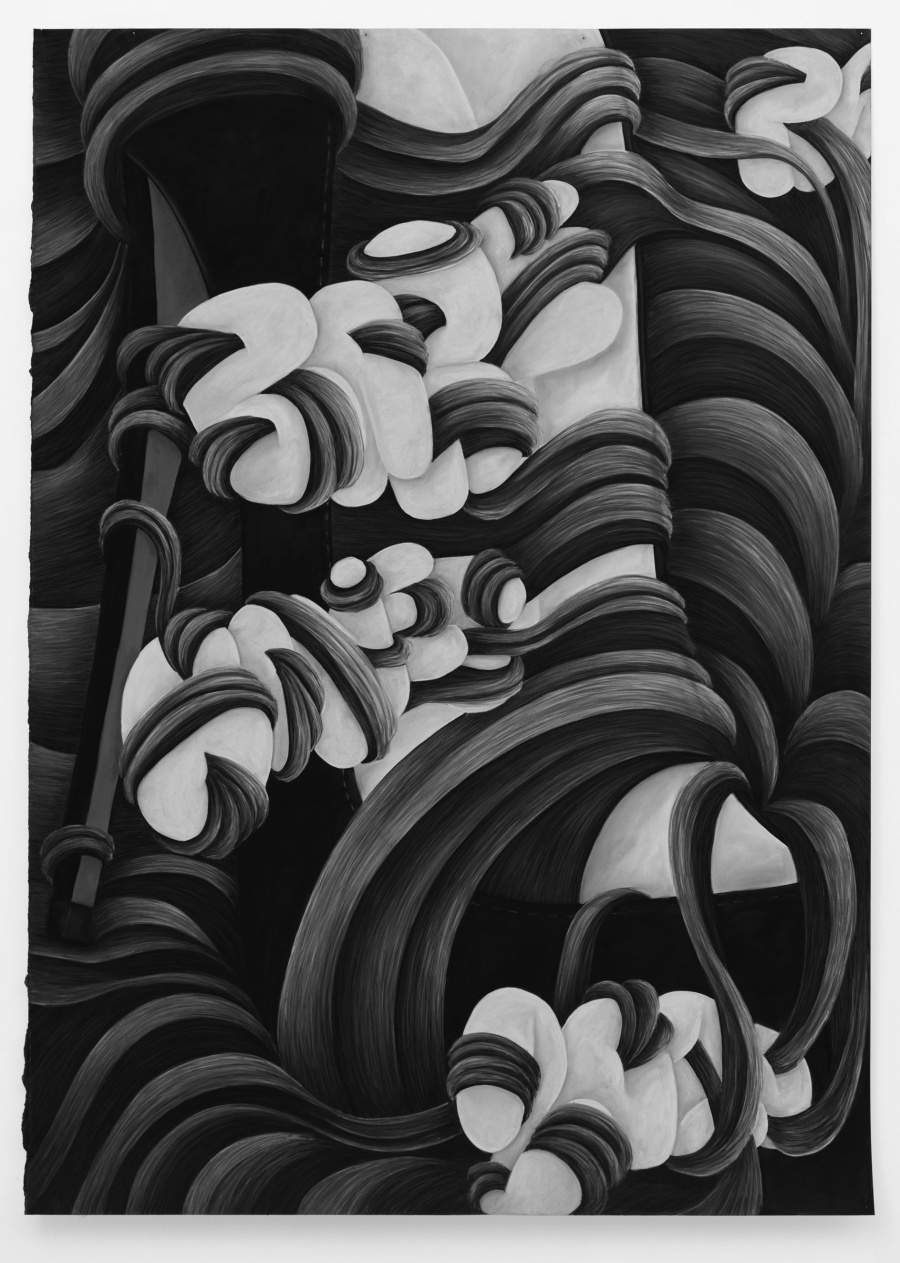

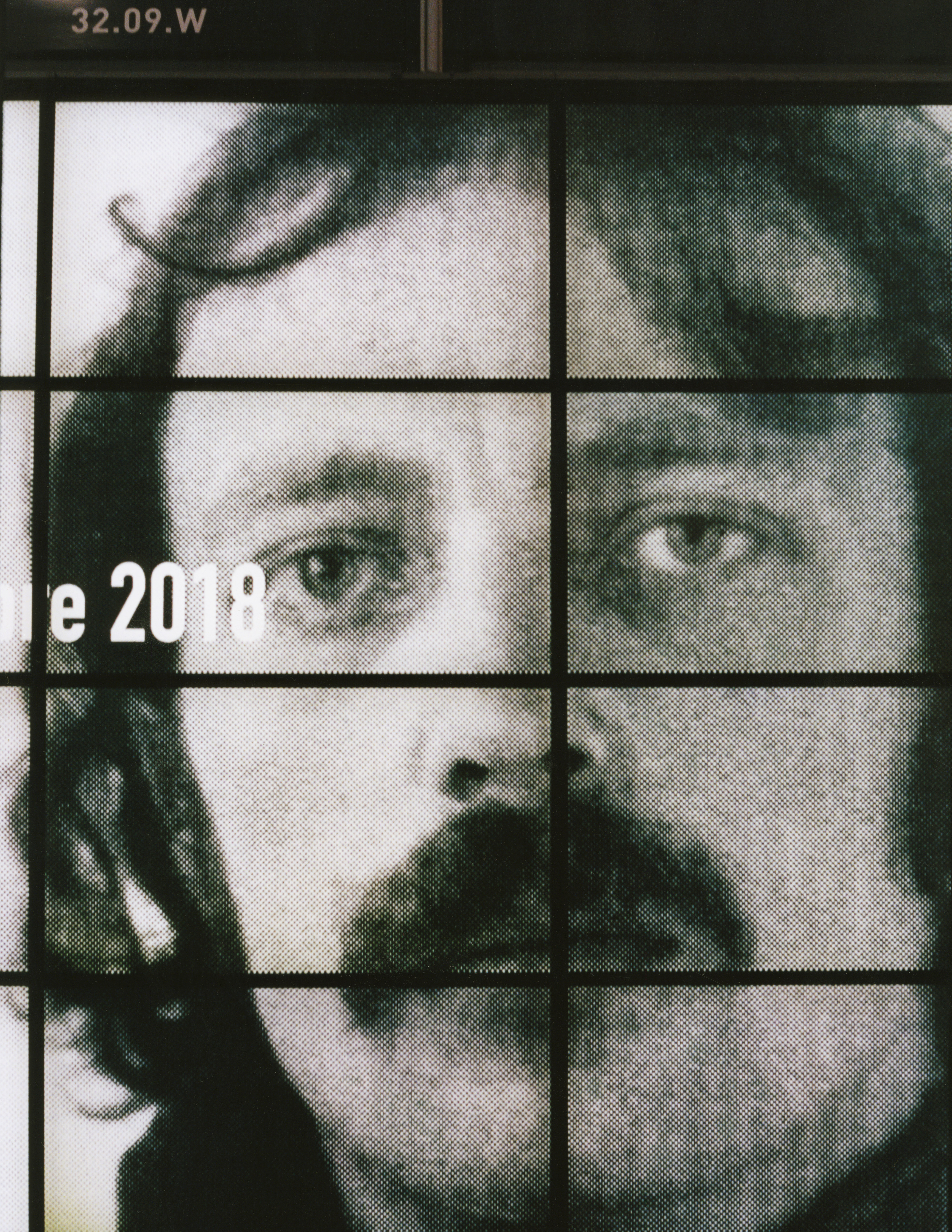

Photos by Tung Walsh

GM:

I’ve been handed a sheet of paper and the first thing I see is something I didn’t know about you. It tells me that you once lived in Jerusalem…

EP:

‘Lived’ is slightly over-egging it, perhaps — I did a student exchange there for half a year when I was an undergraduate at Slade. There was a list of places where you could apply for the exchange, and they were all places that I was fairly sure I’d go anyway. I decided to go to somewhere that I was less likely to visit, and Jerusalem leapt out at me.

GM:

And what was it like?

EP:

I was there in 2004-05. The tension that exists there was just palpable: you’d see evidence of it constantly; people walking around with guns — literally, walking around the streets with guns — or memorials for explosions, or cordoned-off areas where there were bomb-scares. While I was there, Yasser Arafat died. So I don’t think it’s overdoing it to say it was a life-changing experience. It’s also when I stopped making paintings, and started experimenting in other media — my first ever performance was while I was at Bezalel, actually, which is set up in a way that’s completely different to London art schools. You go to classes, and you have a teacher, and there are people smoking in the class: in some ways, it’s like what you imagine art school to have been like in the 1960s, and then in another sense it’s really modern.

GM:

You say you started your performances in Jerusalem?

EP:

When I started at Slade, I was making paintings, and then in my second year I was starting to try to make paintings that didn’t take the form of paintings, as we understand them. And then when I was in Jerusalem, I thought: “This is a waste of time, messing around with little ideas. I want to make big, expansive work about big, important things.”

GM:

You didn’t just make those transitions that some people do — degree course to MA, to big wide world. You’d been travelling a fair bit.

EP:

I was born and raised in Finsbury Park, and went to art school in London as well, so afterwards I took loads of opportunities to get as far away from London as I could. I did two exchange programs: one in Jerusalem, and one at Yale, and then when I left the Slade I did a couple of money jobs and kept showing with my friends, in our homes, and in cobbled-together shows in vacant spaces. And then I moved to Rome, where I was very lucky to get a place on that residency [at The British School]. So that was another very pivotal event.

GM:

Tell me about Rome.

EP:

At first I found it quite difficult, because I’d been showing in a way, and thinking about work in a way, that was defying a kind of establishment, and Rome is all about convention and conservatism, and living in the shadow of tradition. But I did one year at The British School, and then I lived out and about in Rome proper, and had a different experience in that I had no money. I lived in about seven or eight different flats in the course of one year, in various different parts of Rome, and in the end I loved it — I loved every second of it. The moral of the story is that I came to really love what I had started out resenting. I still hate tradition and I hate authority and I hate establishment, but I’ve also come to realise that those things can be really quite useful.

“I came to really love what I had started out resenting”

GM:

How many records do you have?

EP:

Not as many as you’d think. Maybe five-hundred, or a thousand?

GM:

I grew up with records myself — my father was a radio producer, and so I just loved being surrounded by records. It’s a shame to think that vinyl may disappear one day.

“CDs are pretty inconsequential now.”

EP:

Yeah, but the thing is: it hasn’t gone. A lot of the musical formats we’ve listened to in the last ten-or-twenty years are going to fade away — CDs are pretty inconsequential now, for example. But they don’t do what vinyl does. Vinyl has a unique sound, and that tactile physicality…

Read more in Modern Matter issue 7, Postmodern.