© Urs Fischer, photo: Stefan Altenburger, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

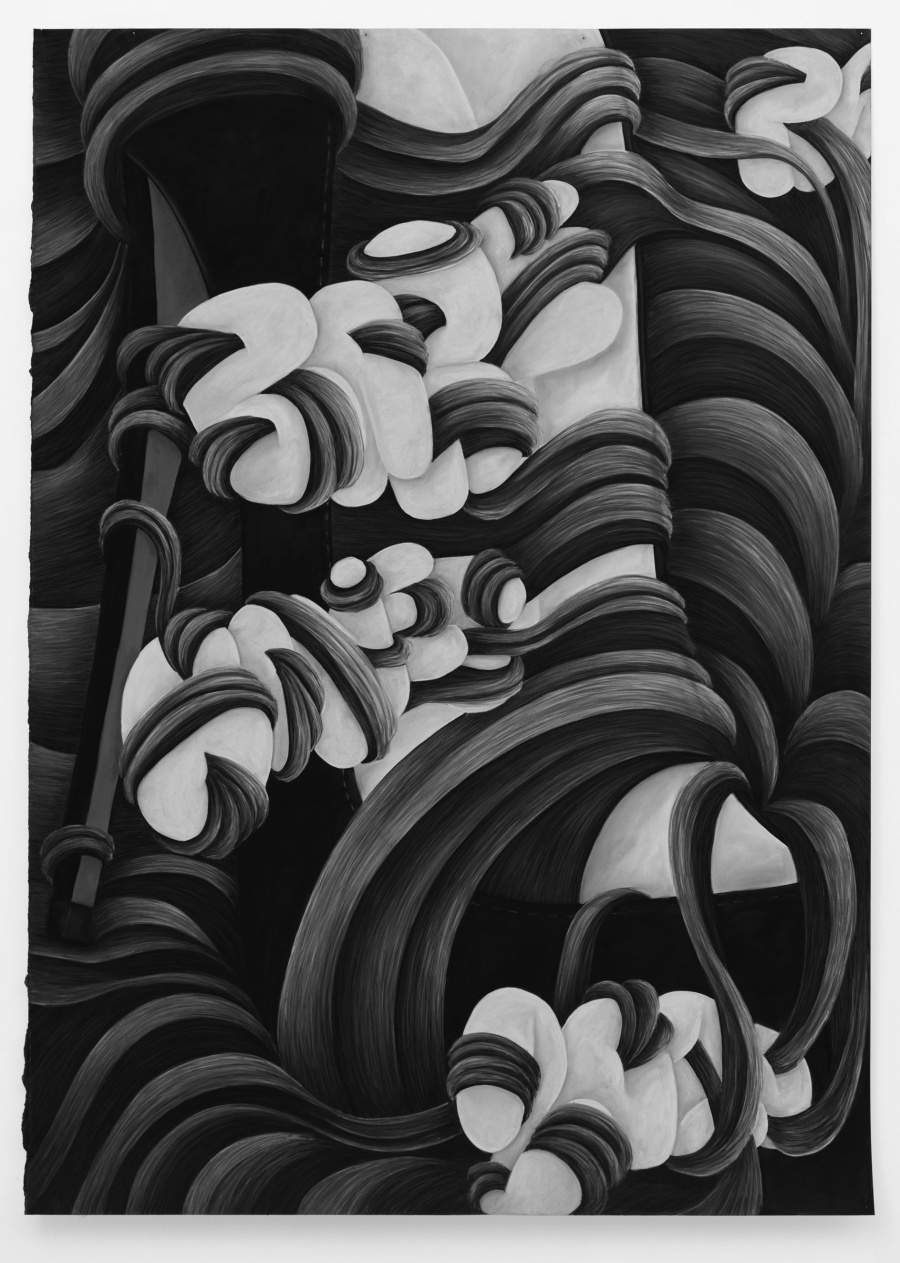

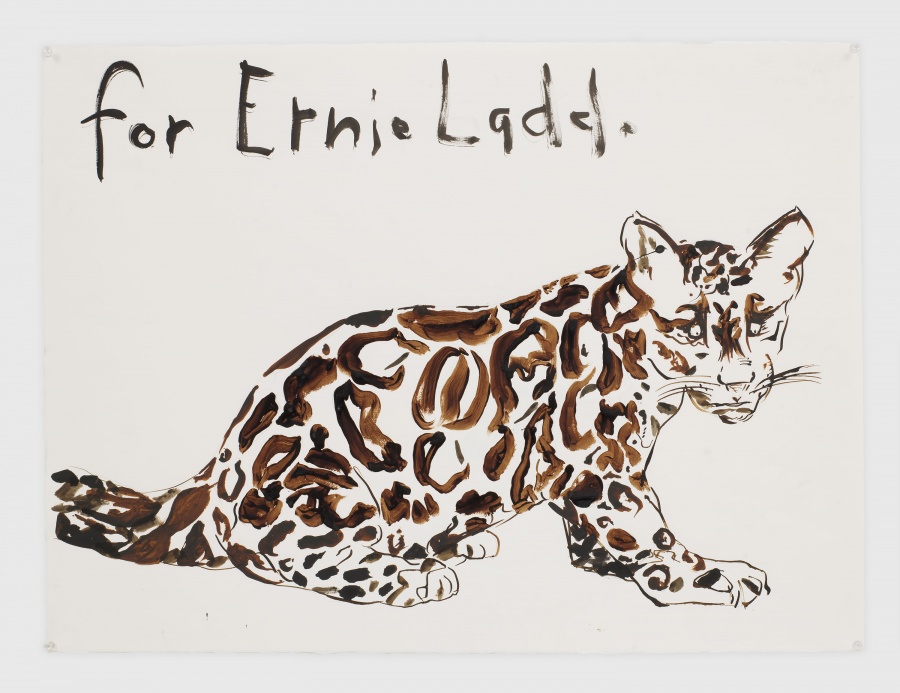

Modern Matter’s editor-in-chief, Olu Odukoya, met Urs Fischer in a bar by chance on a trip to Zurich, and there, they had a discussion about what linked the artist’s wildly heterogeneous and disparate practice, and how visuals could be curated from that. Odukoya suggested that all of the artworks which he particularly liked of Fischer’s were ones which were included some representation – however abstract – of women: black-and-white silver screen starlets covered by slices of fruit, or warped nude figures, or a drawing which suggested a girl’s open mouth and tongue. While female figures might not be the first thing a viewer may think of when they think of Urs Fischer, it was agreed that they formed the basis for some of his most striking works. On returning to the UK, Modern Matter received an email from Urs Fischer, laying out an idea for a visual essay that he had devised from their conversation. The subject line read: Girls, Old And New, and with this in mind as a theme, Olu Odukoya edited a selection of Fischer’s work – all of which contain some abstract-or-literal representation of girls – for Modern Matter’s sixth issue, a year after discussion with the artist first began.

Until 3rd November, Gagosian is presenting the installation “Dasha” – a larger-than-life-size paraffin and microcrystalline wax sculpture of the Czech-born beauty and friend of the artist Dagmar Kozelkova – known as Dasha, and the piece recalls the quixotic seduction of Fischer’s older works, showing that his representation of the female form still veers in perplexing and fascinating directions. In the artwork, Dasha is seated in a chair, and wears a pink dress that stops at the foot of her heeled sandals. A series of wicks have been placed strategically on her body that will eventually reduce her to a melted candle – a show of materiality that runs through Fischer’s œuvre. This process asks the viewer to consider the gravity and momentum of life and mortality, which is then juxtaposed with the minimalism and beauty of a one-piece installation: memento mori à la Urs Fischer.

© Urs Fischer, photo: Stefan Altenburger, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

Dasha herself is an interesting character: the former wife of Roman Abramovich, owner of the Garage, which the Guardian has referred to as “the Moscow equivalent of the Tate Modern,” and the editor-in-chief of Pop magazine; it feels reductive to introduce her through her ex-husband, but she is also at the helm of two major institutions without any previous arts or journalistic experience. That is not to say that she is not intriguing: her capacity to make good business choices has cemented her place in the fabric of the global arts scene, to the dismay of critics. Her beauty and socialite-level friendships – the Serpentine’s Hans Ulrich Obrist is a fan – have further made her a tabloid favourite. It feels natural that Dasha should find herself the subject of her friend’s sculpture, her elegant figure sitting comfortably in her glamorous attire.

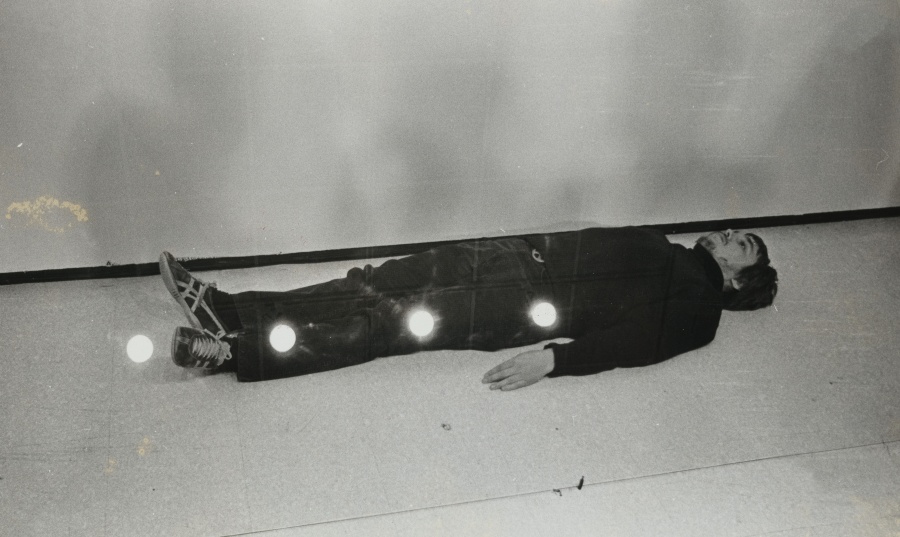

It is not unusual for Fischer to base his works on a friend: in fact, this has long since been a definitive feature of his practice, along with his fascination with mythology. Aside from the incorporation of personal aspects of his life, Fischer is difficult to pin down: since Fischer began showing his artworks in the mid-nineteen-nineties, his practice has expanded to encompass a multi-faceted and playful body of pieces, from slow-melting wax sculptures to birdfeed bread houses. He has shown his works at the New Museum and The Museum of Contemporary Art, and is a regular at Sadie Coles and Gagosian, with the latter dedicating the entirety of its 2018 Frieze exhibition space to Fischer, showing a collection of his large-scale mirror paintings, alongside two small space dogs. He now dominates a corpulent share of the gallery scene, and his work is worth seeing, not only because it is visually stimulating, but also because Fischer understands popular culture – and plays with it.