A Conversation with Gabriel Kuri

30.05.19 | Article by Daniel McClean | Art, interview | MM13 Click to buy

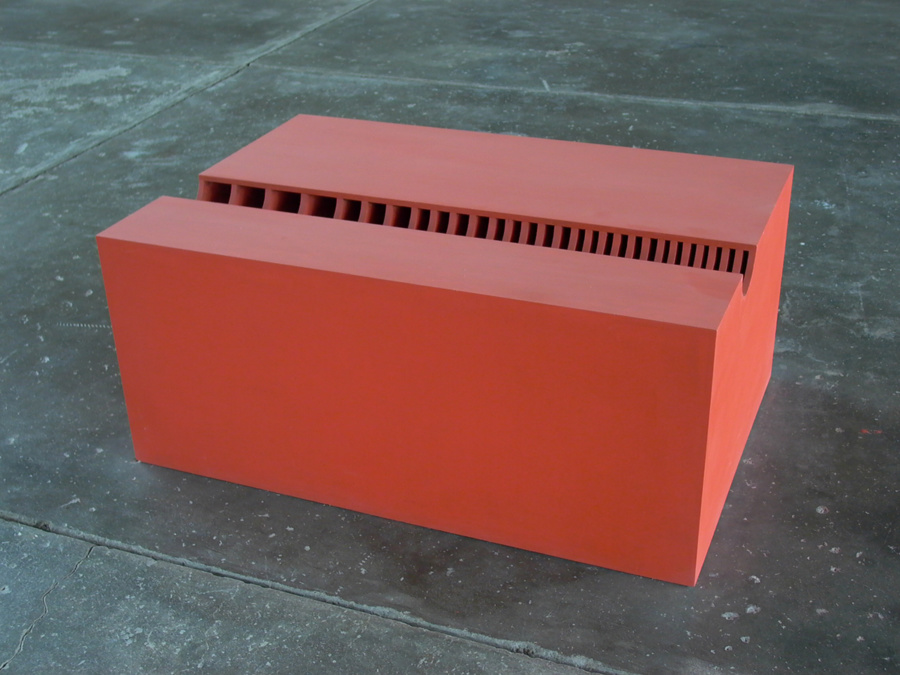

Retention and flow pop up chart, 2009.

DM: I’ve been looking at the images of your beautiful show at Sadie Coles, and as always it has a slightly obscure and paradoxical title: so I wanted to begin by shedding some light on how this description, this title, relates to the show, and what the purpose was behind your choosing it. Afterthought is Not Binary — what are you getting at with that?

GK: It’s interesting that you’d use the word ‘description’. I think that with exhibition titles, it can be a little bit tricky, in the sense that I like for them to be provocative, suggestive, to rouse the viewer’s interest somehow, and of course to be — in terms of any hint that they might offer about the content — setting them in the right direction. So, with Afterthought is Not Binary, I was thinking basically about the mathematics of decision. There is a certain presence of that kind of gesture in the different families of work in this exhibition; a gesture that is like saying ‘either/or’. There’s a lot of pointing, a lot of that very primal and quick organising of things, and I wanted a title that referred to this. I didn’t intend for the title to be an overarching concept to which everything subscribed

DM: So it’s a way in.

Privacy Standards, 2005.

“There’s really nothing about stainless steel that is like us.”

GK: Yes, it’s a way in. But it’s also important in this show that there is that gesture, that moment, which is often quite brief. It doesn’t mean that the work comes out of nowhere, just by chance or very quickly; there is, of course, quite often a very long buildup, and sometimes there is not quite such a long buildup, but there is still baggage. There are a lot of factors that come together. And then, the moment of execution of the work is often brief. And I would hope that it has the gravity and the urgency of a decision that’s taken in one moment. A sensation that there’s something at stake, and that a decision has been carried out.

M: That’s a very nice way of putting it: your work deals with time, and with articulations of time, and obviously an exhibition or the making of a work is the unfolding of various temporal processes, just as you’re describing. You have the immediate physical manifestation, which may be brief; but that might be the residue of a long process that’s been borne out over time, and borne out of thinking and reflecting, out of experience. In light of what you’ve said about the genesis of this recent body of work and of the exhibition, what kind of moment in time does it represent in terms of your practice?

GK: Well, it’s an exhibition that had a really long period of incubation. I had not had a major one-person show in a little while. Very often, the life and career of artists these days means that no sooner have you placed the last little pebble in your current exhibition, you’re forced to be looking ahead — shifting your mind towards another project. In this case, it was not like that. In this case, I had enough time for certain ideas, and certain materials, certain impressions; for certain concepts to really come to maturity. I feel that I somewhat arrived at a place that I had been cultivating and foreseeing for a really substantial period. It’s also an exhibition that is very much of materials and about materials. Its materiality, I think, to a very large extent speaks for itself.

Sin titulo / Untitled (Olas sobre piedra), 2007.

DM: Can you say a little bit about that? One of the things I love about your work is this materiality, but also the way that materiality aligns with metaphor, and the contradictions that you articulate; the tensions between things that give the impressions of being opposites, but are not necessarily opposites. Hard and soft are important dynamics in your work. Nature and culture. The durable and the ephemeral. You often stage these plays between polarities, which may seem at first glance contradictory, but which actually maybe aren’t meant to be conceived of as binary.

GK: I think perhaps what happened in terms of materials in this exhibition, happens quite often in my work — that it came together in terms of contrasts. When I say it explains itself, in reality, I think that what I mean is that it can be seen in very visual and very obvious ways, but also in more subtle and complex plays between materials. Let’s take one of these materials as an example — stainless steel. As we know, it’s a heavy industrial material. It is not something that every artist would have the facilities to work with in the studio, so it is probably understood that these pieces — or at least, part of these pieces — are outsourced to a heavier industrial environment.

“People leave traces behind, our bodies are messy, so there has to be a material that is able to endure this mess”

DM: Is this the first time you’ve worked with stainless steel?

GK: No, it’s not the first time. I’ve worked with stainless steel contraptions that I have purchased. I have also had some of these contraptions altered or enlarged — or let’s say ‘remade’, to look exactly like products of industrial design, or industrial production, but with significantly different scales, or unfamiliar features, so that they felt familiar, but not comfortable or functional. Stainless steel interests me now for the same reason that it has interested me for a long time — it’s a material that I find very attractive in public spaces. I’m talking about public spaces like toilets in airports or train stations; and naturally also, in any space where there is a frequent and heavy flow of people, again like airports, when you’re passing through a security checkpoint. Often there you have stainless steel structures, because so many people are passing through. And of course we know what that entails in terms of materials — people leave traces behind, our bodies are messy, so there has to be a material that is able to endure this mess and that is easy to clean, and is easy to maintain, and is hygienic, and so on. The paradox of a material like this, which is so alien to the human body — there’s really nothing about stainless steel that is like us, or like anything that is inside our bodies — is that this alien nature is the reason why it is so often close to our flesh. So it is not difficult to think of it as being cold, but also as being something that is always near. There is an almost intimate, very direct relationship.

Especulaciones (Analisis de riesgo I), 2007.

Coin and cigarette butt board HS-RP01, 2014.

DM: It strikes me that with regards to the scale of your work, you’ve really captured that intimacy. You’ve really unfolded that, and described that with the scale of those works. Because they can be walked around, and they’re around the height of the knee…

GK: Yes, there is a strong feeling of ergonomy. They are made precisely to make walking around them or reaching down to touch them easy. Just like countertops in self-service restaurants, which have a certain height, and which have dispensers which are spaced out at comfortable intervals. I was trying to follow this logic; the logic you would obey with these kinds of surfaces. I was trying to recreate this impression of a material contrast between stainless steel and then, suddenly, in the case of these self-service restaurants, the coloured paper of sachets of salt and pepper, for instance. And also somehow that moment you make the choice, which is a moment of — I don’t know whether I would say intimacy, but I would say that it was a moment of affirmation, when you ask yourself a very simple, almost automatic question of this kind. I was talking about the mathematics of decision-making, and those decisions can be as simple as “do I take sugar, or not?”

DM: And what about the placement of objects within the work? Tell me a little bit about the selection process.

GK: You were saying that there was a certain intimacy in the knee height, et cetera. For me, part of the long process of incubation that I had with these works took me on a journey through a lot of prototypes. In fact, I tried out a lot of different materials for these boxes — and I do call them boxes. And one of the moments in which I realised that I really needed to work, and that I really needed to make something become, was when I was having trouble with them — and they were larger then, these boxes, these cubes — coming across as plinths. Surfaces that were serving a purpose whereby they were simply support for another object, with that object being the only subject of interest. So I worked a lot on the materials, and on the fact that they have cavities, and these cylindrical cups built into them, and on the size and so on, until I felt that they were objects in their own right, and not just supports. It’s important to point out that these spaces, these holes, are recipients, but they are also dispensers. And I think that becomes evident with the materials that I chose.

DM: And are people allowed to touch?

GK: They are not allowed to touch, because I didn’t exactly conceive them as a work whose meaning would be conveyed by touching, or by participation. I think that participation is tacitly implied. It’s a piece that was made in that way, but its life and its meaning don’t depend on its being used. I think there’s enough inscription there of what they do, so that you don’t have to keep doing it to keep them alive.

DM: We could also talk for hours about what it means to make a box. There’s obviously a legacy of minimalist sculpture present, but how important was that to you — inverting the language of minimalism?

GK: I don’t think it’s incidental, but it’s also important for me that they don’t come across as having any intention of quoting art history. There is something about the geometry of them which we know, because we have seen how art has evolved, and we know that this geometry can be traced to this period in which there was a great anxiety to reduce, and to summarise forms to their bare minimum. But I’m not really intending to quote that moment in art history.

Read more in Modern Matter issue 13, The Anti Issue.

Self portrait as negative chart, 2012.